When the time comes for me to close the cover on a reading session, I have rituals to make sure important insights or experiences from my reading have a chance to settle into my life. In his Lectures on Literature, Nabokov states, “One cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader.” Reflection after reading is in a sense when rereading begins; reflection is rereading without the book in hand. Here are some rituals I do that helps me digest what I read.

Reading Log

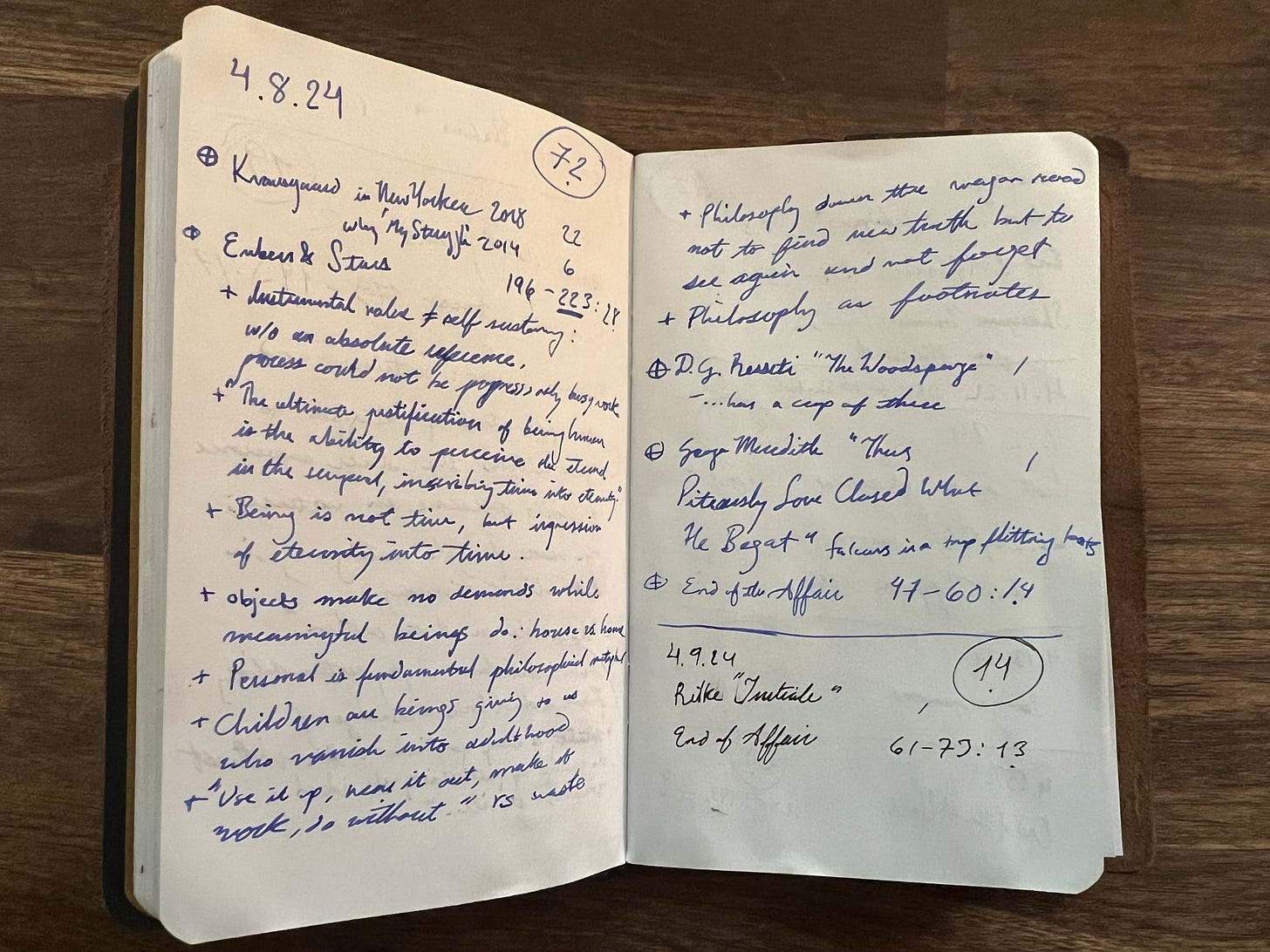

Firstly, I always make an entry in my reading log. This pocket-sized leather cover holds two notebook inserts: one for my reading log and one for a catch all. It’s small enough to take with me anywhere; it’s always by my side as I read, and I often review my entries while waiting in line at a grocery store or sipping a coffee at a café. Just as a captain logs how far his ship has traveled or other noteworthy moments of his voyage, I log how many pages I read in a day and jot down any quotes and thoughts I might’ve came across.

In that way, my reading log doubles as a modest commonplace book. Especially, when borrowing a book from a library or a friend, I’ll record quotes with a page number; if a section is particularly long, I just note the page number with some keywords and take a picture with my phone to revisit later. Occasionally, I also note my own takeaways or thoughts as succinctly as I can; since this is a pocket-sized notebook, space constraints demand that I be brief in my notes. I write just enough jog my memory rather than replace my memory. For this reason, maintaining an extensive commonplace book has always seemed an unnecessary and onerous labor to me.

By contrast, a reading log is a lightweight and low-effort way for me to record the most rudimentary data from my reading sessions: date, title, pages read, and cumulative pages for a day. At the end of a month, I total up the number of pages and record books I finished during that time. (Remember, entries don’t work like math problems: 1-10 is 10 pages, not 9 pages. You have to add a page to account for the one you started on or finished with. In “1-10:10.”, the period after the total signifies that I remembered add that page.) All I really need to know is: What was read? When did I read it? How much did I read?

Again, this data is just enough to jog my memory, but never enough to become a chore to dread. When I page through old entries, I’m surprised how many details of a session I can recall from these seemingly arbitrary sets of number: “54-86” was a when I was finally settling into the plot; “110-116” was a brief but powerful session that gave me pause; “1-70” was romp that I didn’t want to end.

Similar bursts of recollection happen when someone keeps a ticket stub from the theater, a stamp on a passport, or a souvenir sitting on the desk or dangling from a keychain. I’ve even heard of people who read old train schedules to remember trips they’ve gone on and friends they visited.

The analogy that mostly closely resembles my entries are the laconic facts recorded on receipts: “1/6, gastropub, $36.76” means nothing to anyone else, but you remember a first date that went well; “3/15, grocery store, $78.90” was obviously snacks for book club and ingredients for beef stew that week; while you can’t remember what book was “4/3, bookstore, $15.38,” it clearly still stings that you didn’t buy that copy of Platonov instead; “8/20, bakery, $18.23” was two cappuccinos, two croissants, and one cool and cloudy Saturday morning coming back from the gym; “9/4, florist, $45.89” was the last bouquet you bought before it all ended.

Rating Books

Finishing a book, like finishing a session, has its own rituals. When recording the final pages from that reading session, I underline the set of page number to signify I reached the end of that book. Then I set down my analog reading log, and log on to Goodreads to digitally log my books. Again, I keep things pretty lightweight: skip writing a review; just record the date finished and give the book a rating out of five stars.

If you’ve ever perused Goodreads highest rated books, you might gather that people are awfully generous with their 5 star ratings. The galaxies of stars showered on some of these vapid titles might also suggest that the five-star system has been emptied of any meaning whatsoever. While my generosity might not seem as stellar as other readers, I still do love the five-system; there’s an elegance in breaking down my books into tiers that can be counted on one hand. Here is the logic behind my ratings:

★★★★★: This book changed your life. It is now a canonical book for you, and it should be treasured and revisited regularly. In a way, your life is perpetually rereading this book through living out the changes it wrought in you.

★★★★☆: This was a great book, with much to recommend it and it will probably be revisited. Maybe you’ll dip in and mine sections of it in the future, but you’d be glad to read it cover-to-cover again as well.

★★★☆☆: This was a good book which accomplished what it set out to do. You can probably get by with just your memory or a handful of notes. Find the handful of things that interested you and tuck them away for cocktail party conversation.

★★☆☆☆: There might’ve even been a few good ideas, but things went off the rails somewhere. The book jacket might’ve been written better than the actual book. In any case, know exactly why you disliked it: anyone can know why they like something, but wiser readers know why a work failed. You might even grow more through these two-star books than your better-rated books; maybe these faults will guide you along some via negativa to a vision of what the author glimpsed but failed to bring to light. Maybe you’ll see a way to do that idea better.

★☆☆☆☆: They didn’t even have a good idea. This is a waste of your time. If you don’t do book review or have book discussions where this was required, you probably should’ve thrown the book across the room instead of finishing it.

Three Tiered Notes

Finally, there are times when I will reflect on a book and do an outline. For most books, I’m content to just flip through my reading logs or let my marginalia call out important sections. But sometimes, I’ll outline a book to demonstrate that I’ve grasped the logic of an argument or the plot of a novel. In grad school, I discovered Cornell notes and appreciated how you’d put a question on the left and a distillation of the book’s answer on the right, in order to quiz yourself before exams. In a similar fashion, I developed a triple column approach to notes wherein I jot down:

What actually happened, put as simply as possible

Memorable quotes, in the author’s own words

Your personal takeaways from the reading

For example, here is how I would do three tiered notes for Graham Greene’s absolutely haunting novel, The End of the Affair:

Bendrix both loves and hates Sarah, because she suddenly and unexplainably broke off her affair with him.

“Hatred seems to operate in the same glands as love: it even produces the same actions.”

You can only truly hate someone you’ve first loved them; there is no hate without a prior love. When some misfortune or betrayal befalls a relationship, the suffering causes the love to sour into hate.

This outline system makes sure you cover all the bases. You can use it on a section-by-section basis or for a book as whole; at any given point, it helps to separate the facts of what happened, important quotes, and personal thoughts. Unfortunately, in university days, my younger self often become so consumed with his personal thoughts on a work or wasted tons of time laboriously stashing quotes for citations that he’d fail to remember big, dumb, simple facts like “How did it end?” Likewise, attending to that level of sheer fact helps ground which quotes are essential to memorize from a work and which are just pleasant or interesting. Pick a book and draw three columns and fill the facts, quotes, and your thoughts on the work as whole. Then feel free to break each of its major acts or sections up into these three tiers. Even just doing it on the level the book as a whole should give you a demonstrable foothold in remembering what you read, and remind you what is worth revisiting.

Links

Vladimir Nabokov’s, Lectures on Literature

Erazim Kohák’s, The Embers and the Stars

My pocket-sized leather cover & notebook inserts

Graham Greene’s, The End of the Affair

This seems so doable, thank you Sam. Could you say a few words about the symbols in your notes? What kind of entries do they signify?