“Read Attentively,” The Level of Experience

"Read Like Lonergan" Series, Part I: Sleepreading, subjectivity, collaboration, physicality, different formats of books, and notes.

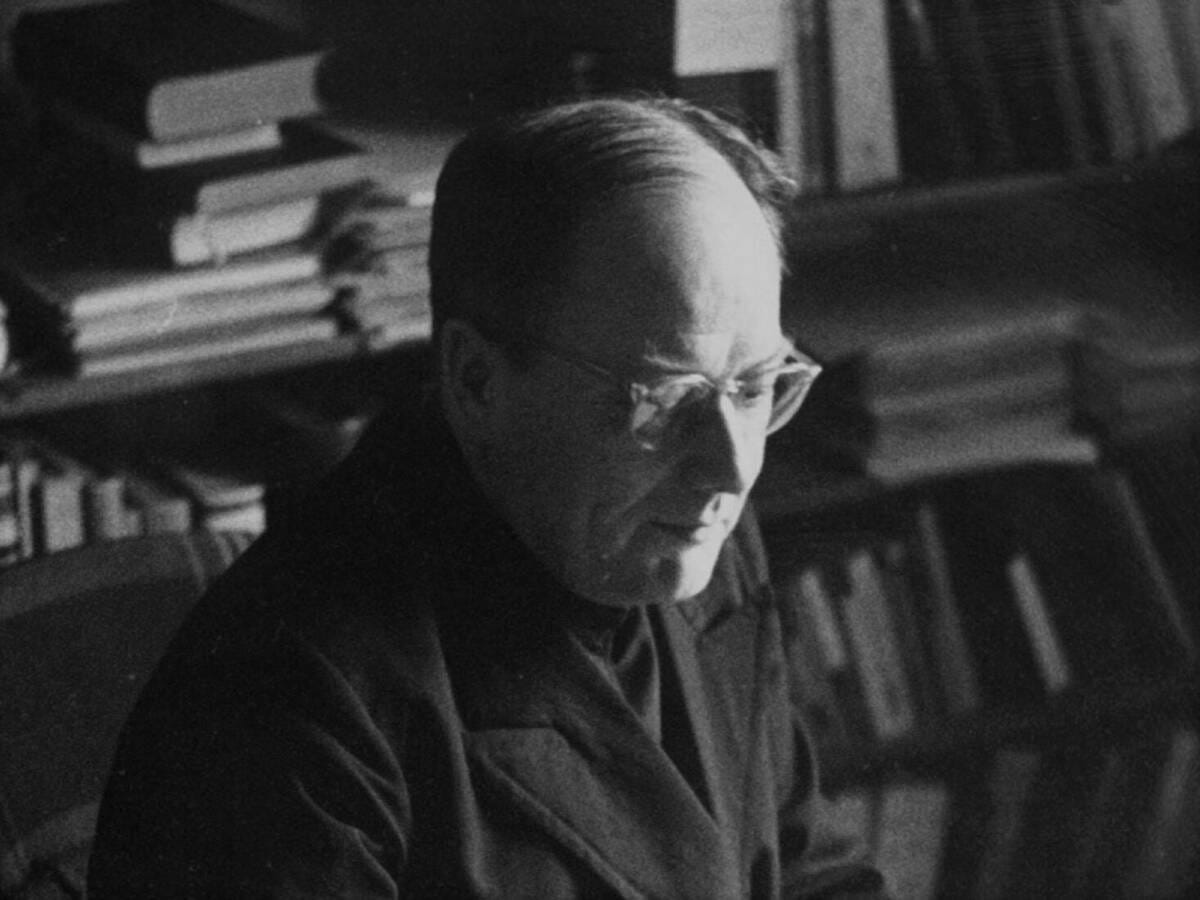

In this post, we continue our series exploring how the philosophy and method of Bernard Lonergan, S.J. can help us to become more attentive, intelligent, reasonable, responsible, and loving readers.

§1 Sleepreading

At the end of the year, we might find ourselves staring at our shelves or our lists of books read, blankly. Maybe there are some impressive authors or titles there. Maybe it’s an impressive number of books. Maybe we spent countless evenings over months reading some of the larger volumes. Maybe we even filled their pages with marginalia or recorded tons of reflections in our notebooks. Despite all that, basic questions might still haunt us: “Wait, how did that novel end again?” “What was that philosopher’s argument exactly?” “I remember liking that poet, but why can’t I recall a single line off the top of my head?”

This sense of emptiness suggests that we might’ve missed something essential to being good readers. Sometimes bad intentions can keep us from truly enjoying a book. Perhaps you don’t actually enjoy the act of reading itself—you just enjoy being someone who can say they have read certain books or a certain number of books. At times like this, reading a book just means finishing a book or checking it off a list. In another sense, we can often be so busy trying to get something out of a book that we forget to let ourselves get into the book. We get through many books, but few of them ever get through us.

To remedy this emptiness, we must first attend to our reading on the level of Experience. In Lonergan’s four-fold method, all of the other conscious actions are grounded by Experience and Attention. As the Peripatetic Maxim of Aristotle and Aquinas states, “Nihil est in intellectu quod non sit prius in sensu—Nothing is in the mind that was not first in the senses.” The depth of our attention determines the quality of our experience, which in turn shapes the content of our lives.

When we fail to pay attention, we become what Lonergan calls “somnambulists”—simply sleepwalking through life unawares. If we feel empty when reflecting on our reading, perhaps we didn’t give the book our full attention. We might have spent a lot of time with a book, and yet we weren’t all there. We were just turning pages and killing time. We were sleepreaders.

Before we can understand a book, we must first read it—we must first experience it—and we must do so attentively. Here’s how we can do that better.

§2 Patterns of Experience

First, we must answer the question: What is a book? Many people might think of books in the same way that they would think of a objective container of objective things. In this sense, we think a book holds ideas as a wallet holds money; books hold characters as a cave holds jewels; books hold insights as a garden holds potatoes. Perhaps, we think we can reach into a book and pull out something, but it turns out there’s actually nothing in there.

Books are nothing but piles of paper and ink—until we read them. Then they become enlivened by our attention, and the printed letters become characters, the paragraphs become themes, the book becomes a world. There’s nothing objective about reading.

Books are patterns of subjective experience which authors share with us. Even when advancing the most objective, factual argument, an author does so in a subjective way. Through their book, they essentially say: “Here, stand in my shoes, sit at my table, breathe my air, think my thoughts, feel what I feel, live my life.” Reading offers us the chance to live a different life, in a different world.

The work of art is an invitation to participate, to try it, to see for oneself… the work of art invites one to withdraw from practical living and explore possibilities of fuller living in a richer world

Lonergan, Method in Theology p. 64

When we read, we enter into a form of sympathetic attention with the author. This shared attention—this pattern of experience—allows us to collaborate with them in the imaginative creation of a world. The author’s world enters into us as we enter into it. Books are not monologues but dialogues; reading is a conversation co-created between reader and author.

Being an attentive reader does not necessarily mean being a focused reader. In fact, too much focus can constrict our attention and cut us off from authentic experience. Instead, we should open ourselves to the unknowns that come with our books. Set aside preconceptions about who you think Tolstoy or Dickens is. Let the author tell their story as if for the first time—because for you, it is the first time. Practice hospitable reading. Welcome the author into your life and allow yourself to be welcomed into theirs, even if only for a few pages.

Whether or not we agree with the author or even like him is irrelevant at this stage. You can’t truly know what you think about a book without first reading it. Again, Experience grounds everything. In order to be a more attentive reader, you need to not jump to the level of Understanding, Judgment, or Decision without first establishing the level of Experience. We can disagree later, but now we first must listen.

§3 Embodied Readers

What is one of your favorite quotes? Take a minute to call it to mind. Now, what do you see? In answering this question, many of us can remember exactly where on the page it was. Perhaps it was on the right or left page. Maybe we can even recall how close it was to the beginning or end of the book.

Books, like us, are three-dimensional beings. They exist in the physical world, and we experience them in a physical form. Thus, our reading and attention encompasses more than just words: there is an embodied, incarnate character to our experience. Notice the curves of the book's typeface, its size and weight, the texture of its cover. Beyond the book itself, consider the quality of light in the room where you're reading, or the flavor of tea you're sipping between chapters. None of these experiences are technically “in the book,” yet they are crucial for forming our relationship with it.

These seemingly insignificant elements provide essential footholds for our memory to revisit these experiences later on. They create the context within which the book's content sits; they are the frame which directs our gaze to the picture that we and the author depicted together. Bernard Lonergan called these arbitrary impressions the “empirical residue” surrounding our insights. Gerard Manley Hopkins might call it “haecceity” or “thisness.” Each reading is done by a particular person, at a particular time, with many other particularities that make up our experiences. We are uniquely instantiated physical beings, and so is our attention. Without experiencing this book as a physical object, we couldn’t even have a relationship with it.

Consider how much food we consume that comes encased in a shell: pistachios, peanuts, bananas, mussels, oranges, even the wrappers surrounding Halloween candy. While all of these shells are inedible and discarded so we can extract the tasty thing inside, we would never receive the food without the shell’s protection. Similarly, the empirical residue might be abstracted away from our insights, but we would never have those insights without discovering them in the empirical realm of Experience.

There’s another dimension to this food analogy: the ritual of peeling or unwrapping contributes to our anticipation and enjoyment. Would you rather pry open and savor your mussels one-by-one, or shovel a bunch of them in your mouth at once? Would you prefer a bowl full of unwrapped chocolate bars, or does the crinkle of the wrapper whet your appetite? There’s a friction to the empirical that awakens and heightens our attention, making us more present and the experience more enjoyable.

§4 The Media of Books

For all these reasons, I struggle with digital books. Our devices remove much of the physicality of books in an attempt to serve up pure content. All the normal empirical markers that help me orient myself within a book are gone: typefaces or text size change on a whim; we can toggle between light mode and dark mode; we can flip pages or scroll through text. Because everything is fluid, everything moves around when you change a parameter. The only way you can find anything is to use the search function. It’s disorienting when things are disembodied.

That being said, I recognize there are situations where stripping away that empirical residue can actually be beneficial. A few years ago, I started reading Don Quixote while traveling the Spain on trains—by reading it on my phone. Cervantes’ classic is a notoriously hefty tome, and I didn’t want to lug it around in my satchel. When I finally opened my physical copy to resume reading at home, I was shocked to discover I’d read several hundred pages on my device. Similarly, on a recent vacation, I began reading another massive work on my phone—Proust's gargantuan In Search of Lost Time. In both cases, size limitations and convenience led me to adopt the digital copy, yet I still had enjoyable, attentive reading experiences. Why?

With these massive books, the physicality itself might actually impede attentive reading. Proust wrote the longest novel of all time; many regard reading In Search of Lost Time as the literary equivalent of scaling Everest or running the Boston Marathon. The same applies to Cervantes, Hugo, Melville, and most of the Russians. With expectations like these in our minds, holding one of these hefty volumes can turn reading into an intimidating experience.

But when I had all of Cervantes and all of Proust downloaded onto a slim phone that I could slip into my pocket, they felt more approachable. We give hours of our attention to our devices, scrolling through miles of digital content daily, and we do so effortlessly. Why not slip in a few windmills and madeleines? If you added up the text you’ve consumed through various feeds, you could have read all of Dickens, Dumas, and Dostoevsky several times over by now. While I recognize the experiential and mnemonic benefits of physical books, in these cases, removing the intimidating physical presence made me a more receptive reader. After all, fear and expectations can disconnect us from Experience, so removing those barriers can enhance our engagement with the book at hand (or on device).

I’ve also had profound experiences with audiobooks. Humans have been telling stories and expounding theories in conversation long before we thought of writing them down. Most of us were read to as children, and reading aloud is a natural phase in our development as readers. Therefore, listening to books can create immersive and attentive experiences—even if they're not technically “reading” in the traditional sense.

While they lack all the physical dimensionality of a traditional book, audiobooks do bring in another essential dimension of our attention: Time. One of my favorite audio experiences was listening to Homer’s Iliad. The first time I (was forced to) read it, I was in high school and it was a dreadful and boring experience. But from the opening lines, Steve John Shepherd’s powerful voice grabbed me by the lapels and shook me with his recitation of Homer’s “wingèd words.”

To this day, I can still recall several verses tinged with the timbre of his voice. While I can’t necessarily point to the place in the book where those verses are printed, I can tell you about the walk I took while I listened to those words, the golden rays of sunlight filtered through rich green leaves of June; I can tell you about how I was lifting weights over my head just as Peneleos lifted his enemy’s eyeball on a spear “like a poppy upon its stalk”; I can remember organizing the junk in my basement while Hephaestus crafted Achilles a new shield that had the whole world engraved upon it. Even though the only dimension in an audiobook is time, it turns out the rest of my world supplied the empirical residue which helps me remember the story—and how the story became part of my life.

Sure, there were many times I was distracted and just mindlessly listened to some chapters in the background. But that’s not the fault of the audiobook; that’s on me for breaking off my attention. Even with traditional books, there have been many times when I realize my eyes have passed over a couple pages and I have no idea what the author said. You can be distraction no matter which medium you chose to experience your books.

Each of these kinds of books has benefits and risks. Just remember that all of them are intermediary steps towards our real goal: cocreating a world with the author.

§5 The Paradox of Note-Taking

Since reading is fundamentally a conversation, we should remember the first rule of good conversation: listen fully to the other person before formulating our response. When we become poor conversationalists, we focus excessively on drawing connections to what we already know or what we care about, thereby cutting ourselves off from truly hearing the other person. We walk away from such exchanges remembering that we had plenty to say but we’re not sure what they said.

Here I must present what might be a scandal to many readers: Taking notes can sometimes be counterproductive on the level of Experience. Allow me to explain.

There’s a rhythm to reading and writing—they are distinct modes of engagement. There’s a time when you need to let the author tell their story uninterrupted, and there’s a time for you to compose your side of the conversation. The question is: when should each occur? When we interrupt the flow of reading to make notes, we risk fragmenting our experience of the text. It’s like interrupting someone mid-sentence to make your point, rather than allowing them to complete their thought.

The act of attending to the author’s words on the page while simultaneously scribbling our own ideas in the margin creates a division in our attention. This split focus often comes at a cost: when we try to remember that exchange later, we might vividly recall what we noted but have only a hazy recollection of the author’s original argument. As this pattern deepens, we risk having the same conversation over and over again, bringing our preconceptions to every book rather than allowing each work to speak to us on its own terms.

Consider what happens each time we underline a sentence: we make a value judgment, deeming this sentence important and worth remembering (and simultaneously rendering everything else less important and less worth remembering). In Lonergan's schema, every note potentially pulls us out of the immersive flow of Experience and prematurely elevates us to the levels of Understanding or Judgment. We move from experiencing the text to analyzing it—often before fully experiencing what it is the book is trying to offer us.

This can devolve into a self-affirming cycle. First, we break out attention from the flow of the book to make our own notes. Then, we isolate the content we find important and discard the context we find unimportant. Both of these together weaken our attention and our ability to recall things later on. But thankfully we took those notes! The notes step in to aid the very memory they hampered; they solve a problem they may have created in the first place. Like victims of Stockholm Syndrome, we feel secure and protected by the very things keeping us captive. Notes seem to help us remember, but they might just make it easier to forget.

Nevertheless, notes have their uses just as much as they have their abuses. Abusus non tollit usum. Healthy note-taking does not sacrifice the level of Experience to prematurely jump ahead to the level of Understanding. When we interrupt our attention and skip the Experience level, we are making unhealthy notes. Again, most of us will never know there’s a problem because the notes seem to help us remember so much. Naturally, anyone who has browsed my posts knows that I’m an advocate for healthy note-taking. Here are a few things I do to take healthy notes:

Employing consistent symbols to make marginalia automatic and effortless. (Save your attention for the book itself.)

Use a pencil and take things lightly. (Both literally and figuratively)

Wait a page or two before making a mark or underlining a section. (Let the author finish their whole thought first.)

Use the Five Tab System to orient yourself in the book without breaking its flow.

Log your reading sessions after you close the book for the day, with a few keywords or takeaways.

Consult the book’s Table of Contents or Index. (Many of our own notes might actually be redundant.)

Every once in a while, read a page with your left eye. (The right eye focuses attention. The left eye opens attention.)

Strategies like these help capture impressions of a book without fragmenting attention during the reading itself. They acknowledge the complementary nature of immersion and reflection—there’s a time to read and there’s a time note. The key is to make your extra-textual work as light and effortless as possible. If you have to break your attention or step out of the book’s pattern of experience to make a note, perhaps that’s the moment to simply keep reading instead. You can always jot down a note later, even if it’s just a moment later. Our notes play a greater role in the next levels of Understanding, Judgment, and Decision. But make sure the foundation of Attention and Experience is laid first.

§6 Conclusion

In fully human knowing experience supplies no more than materials for questions; questions are essential to its genesis.

Lonergan, Insight, p. 277

Before you can understand a book, you must first read it. You don’t even need to understand the author at this point—you just need to be with them. It might take a few rereadings of a book before you can move up to Understanding from the Level of Experience, but you can’t skip it. We might sleepread a book several times before we begin to actually read it. A lack of understanding is a good sign at this stage. Embrace your curiosity, feel the questions well up within you—without trying to seek their answers—just yet. We will learn how to pursue these questions in the next post where we discuss the second level of reading: Understanding.

Until then, simply read the book, experience the book. Read attentively.

Links

Insight, by Bernard Lonergan

Method in Theology, by Bernard Lonergan

Quest for Self-Knowledge, by Joseph Flanagan

If you liked this post, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee ☕

I love to read and this article feels just right for how to increase my pleasure and comprehension of my reading. Thank you!

I find footnotes in fiction distract me from the flow of my reading also. I prefer editions without footnotes for my reading copy. Then I can skim footnotes in an ebook edition if I need to.