Pentatonic Vowels

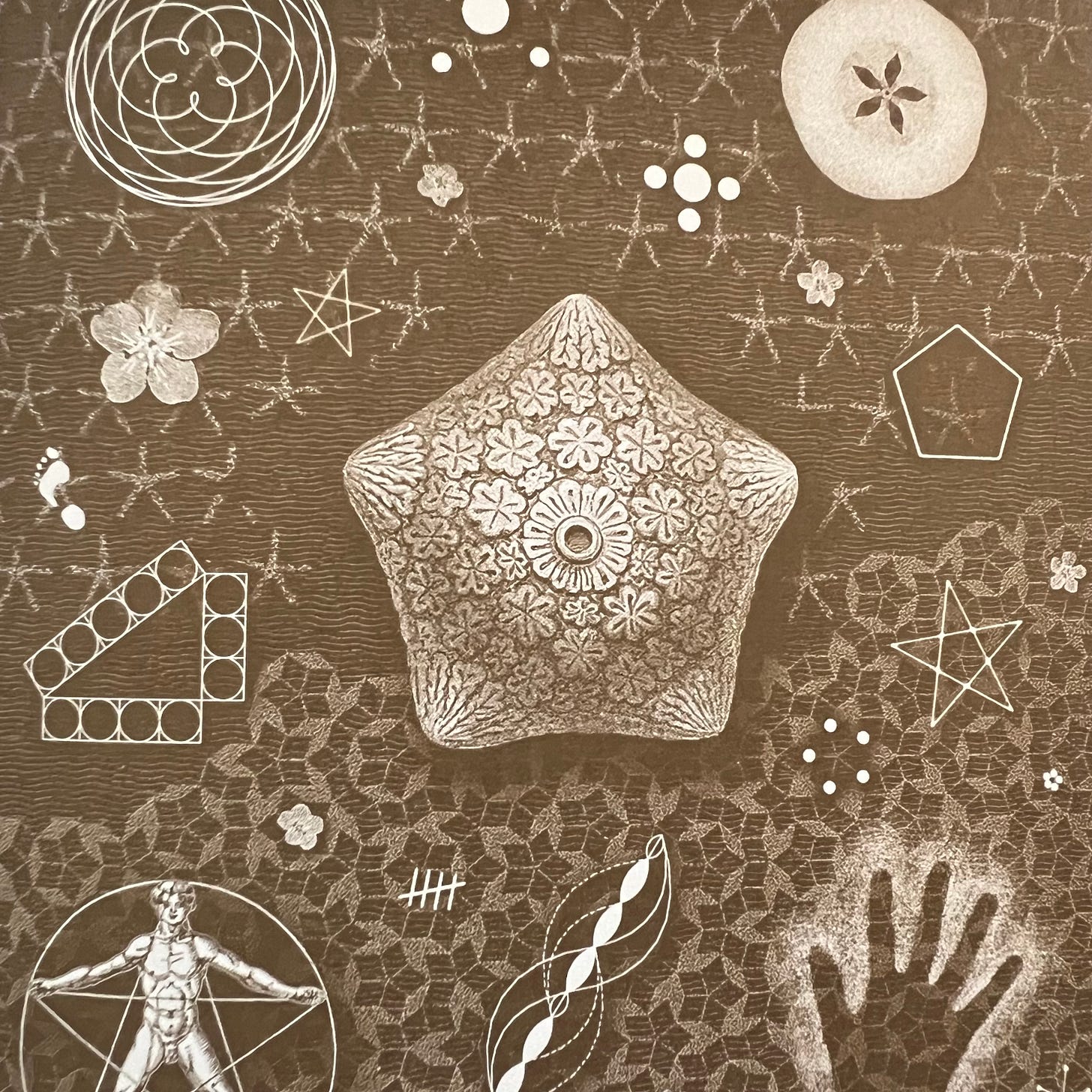

Whenever I wonder why we have five vowels in our language, I marvel at how I can count them upon my fingers. Five notes for five fingers. Isn’t that handy? And if I were without my hands, I could still count these tones on my five toes. From my pentamerous body stretch out five limbs: my two arms, my two legs, and my head atop it all. My head is crowned with all five senses: my tongue tastes an apple holding its fivefold center of seeds; my nose smells roses and the lilies with their pentadelphous petals; my skin feels the five elements of earth, air, fire, water, and aether brush themselves against it; my eyes see the world in terms of the five patterns of Platonic solids; my ears hear the world resounding with the chimes of pentaugic stars and all their pentatonic harmonies. Is it any wonder then that we have five vowels?

The most universal melodic pattern in human music is the pentatonic scale. From the most ancient civilizations to the most banal pop music of own day, every culture has used pentatonic scales to tells stories with their songs: Indian ragas such as Raga Bhoopali; the Arabic maqam Rast Ubeidi; Gamelan slendro tuning; Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox chants; Native American chants; the myriad of Chinese and Japanese pentatonic scales with their slights changes in pitch distance and attraction—and of course the blues. Many of these musical traditions can identify more notes than five in an octave: Western music has the diatonic scale with 7 notes, bebop scales with 8, and the chromatic scale with 12. If one is immersed in the microtonal acuity of other traditions, they might even distinguish the 22 Indian śruti or 72 Byzantine moria which reveal prismatic shades of chromaticisms. But no matter where they decide to place these notes, five are the rudimentary melodic pitches in a scale.

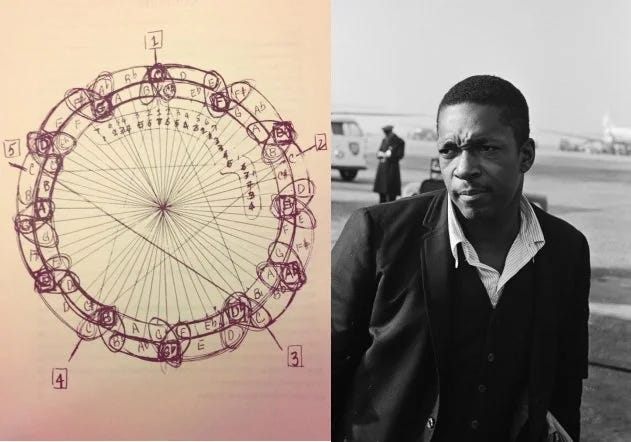

In its most universal form, the pentatonic scale is five notes built from fifths. We discover the five notes of the pentatonic scale by taking the fifth of each note starting from a root, ex. C-G-D-A-E ( ● ▲ □ ○ ∆) which we arrange in order C-D-E-G-A (● □ ∆ ▲ ○). If we continue this pattern we’ll get the next two pitches of the diatonic scale, the seventh B (∅) and the fourth F (■); as the seventh in the key of C (●), B (∅) wants to go either up a semitone to the major root of C (●) or down a whole tone to the minor root of A (○); as the fourth of the key, F (■) is only a semitone away from the third (∆) and draws it to itself. When one begins adding more notes to the pentatonic scale, those additional pitches often serve more as passing tones, which are attracted to the gravity of a more stable pentatonic pitch.

The introduction of semitones offers more shades of tonality, but it also introduces more tension and potential dissonance. Just as the fourth is a fourth above the root, the root is a fifth below the fourth: one man’s fourth is another man’s fifth. In this paradoxical realm, where the solid force of the fourth runs parallel above—or plagal to—the root, it often serves as a kind of key change where its pentatonic scale fractals out, until draws back up a whole tone to the triumphant and precarious fifth of G (▲), which moves us back to the root C (●). All this drama (and potential cacophony) arises from the natural order of harmonics ascending on top of one another, and they naturally want to resolve back to the home note of the root. No matter how tense the harmonic progression becomes, our music keeps its eyes open for the fifth, as those are the North Stars guiding us back to the root. It’s true for all music: whether it comes flows from an instrument or from a voice.

Vocal music is considered to be the highest, for it is natural; the effect produced by an instrument which is merely a machine cannot be compared with that of the human voice. However perfect strings may be, they cannot make the same impression on the listener as the voice which comes direct from the soul as breath, and has been brought to the surface through the medium of the mind and the vocal organs of the body.

― Hazrat Inayat Khan, The Mysticism of Sound and Music

Our languages use five primary vowels just as music uses five primary tones, because our mouths are instruments through which we play our speech. Just as a trombone or trumpet player uses the embouchure of his tongue and lips to drive the air through the tube which reveals the harmonics we hear, so too the human voices is driven through the tubes of our throat and controlled by our tongue and lips; humans are in this sense inverted wind instruments (or wind instruments are inverted humans). Physics dictates that these harmonics are revealed as we pinch the wind as it flow across our tongues and out of our mouths. Say the core five vowels and hear how they don’t so much glissando between one another as reveal next harmonic levels of pitch; feel how the level of the tongue and the aperture of the mouth collaborate to generate these harmonics:

Ahhh… Ehhh… Ieee… Ohhh… Ouuu…

Just as some musicians use more than five notes, some languages have more than five vowels. But these are just variations on a theme. In that they’re running from one of the five vowels to another of the five vowels, it means that diphthongs, pitch accents, and tonal languages differ more in degree than kind. Diacritics serve as the sharps and flats of our letters, marking vowels long or short; when it comes to the letter “o,” Hungarian has four different kinds: o, ö, ó, ő. But Hungarian also has vowel harmony that keeps phonetically similar vowels sounding throughout a whole word: only low vowels like “o” and “a” will run through a grounded word like Magyarország and only high vowels like “e” or “é” run cheerily through a word like Egészségedre. Speaking of harmony, the German letter ü is literally a harmony of vowels; it is what happens when your lips do an “oouu” and you tongue does a “ieee”; we find this same overtone stacking both in the virtuosos of Tuvan throat singers on the plains of Mongolia and whenever a kid simply whistles a tune to himself on the way home from school. Just as harmonics are found along a string, vowels are overtones of the human voice.

Our vowels and the pentatonic scale don’t just have much in common—our vowels are the pentatonic scale as found in our speech. With every sentence, the vowels—aaa, eee, iii, ooo, uuu—fill the space between percussive consonants with clear pitches of sound; they lend our sentences a harmonic structure and weave melodies within our words. But since we had music first, we should say: music gave us speech. Within a given octave, our voices cause infinite frequencies to vibrate, and no one could notate the subtle undulations in even the most common conversation. Likewise, no one has ever played the same note twice. Even still, there’s a pentatonic gravity to each of those notes and our vowels, which in their balance with each other balance all the other tones. All comes from the fifth, all returns through the fifth.

Anyway, enough for today. Let’s take five.

Links

Hazrat Inayat Khan, The Mysticism of Sound and Music

Quadrivium: The Four Classical Liberal Arts of Number, Geometry, Music, & Cosmology