Notebook Processing: Catch-Alls ⨁

Anyone can fill a notebook, but knowing what to do with it afterwards is a more difficult question. Many a notebook ends up in a neglected stack, stored in boxes under beds or down in the basement, where they will languish away until they’re rediscovered during spring cleaning, a garage sale, or a midlife crisis. Personally, all of my completed notebooks stand on a shelf in my office. Every day I look at them and vacillate between the pride of accomplishment and the nagging sense of dread, as I wonder, “What do I do with them now?”

Over the years, I’ve dipped back into them in a very scattershot fashion. While this haphazard approach has its charm, it also frustrates me. There’s too much unrealized potential sketched in these books, and it’s not well-organized. Even if I come across an especially good idea, I start exploring that idea in another notebook, which will also end up collecting dust in my office. Those past thoughts unleash new streams of thought that threaten to overflow the banks of my shelf. Whenever I try to get on top of old stuff, I just end up getting buried in new stuff.

How can I ever get on top of what’s in there? How can I not get lost while trying to find the really good pages? How does my past fit into my present? What can I do with all of these notebooks?

After several years of sitting with these questions, I’ve finally come up with a system for processing my notebooks. In another post, I began to talk about how I process my Reading Logs (◫). And since Planners (⊞) and Journals (≈) are a bit more demanding with their content, we’ll deal with them in their own posts later on.

Today, we’re going to focus on the notebooks that are the easiest to fill and easiest to set aside afterwards: Catch-Alls (⨁). Here’s how I process them.

Process While You Write

Crossing Out

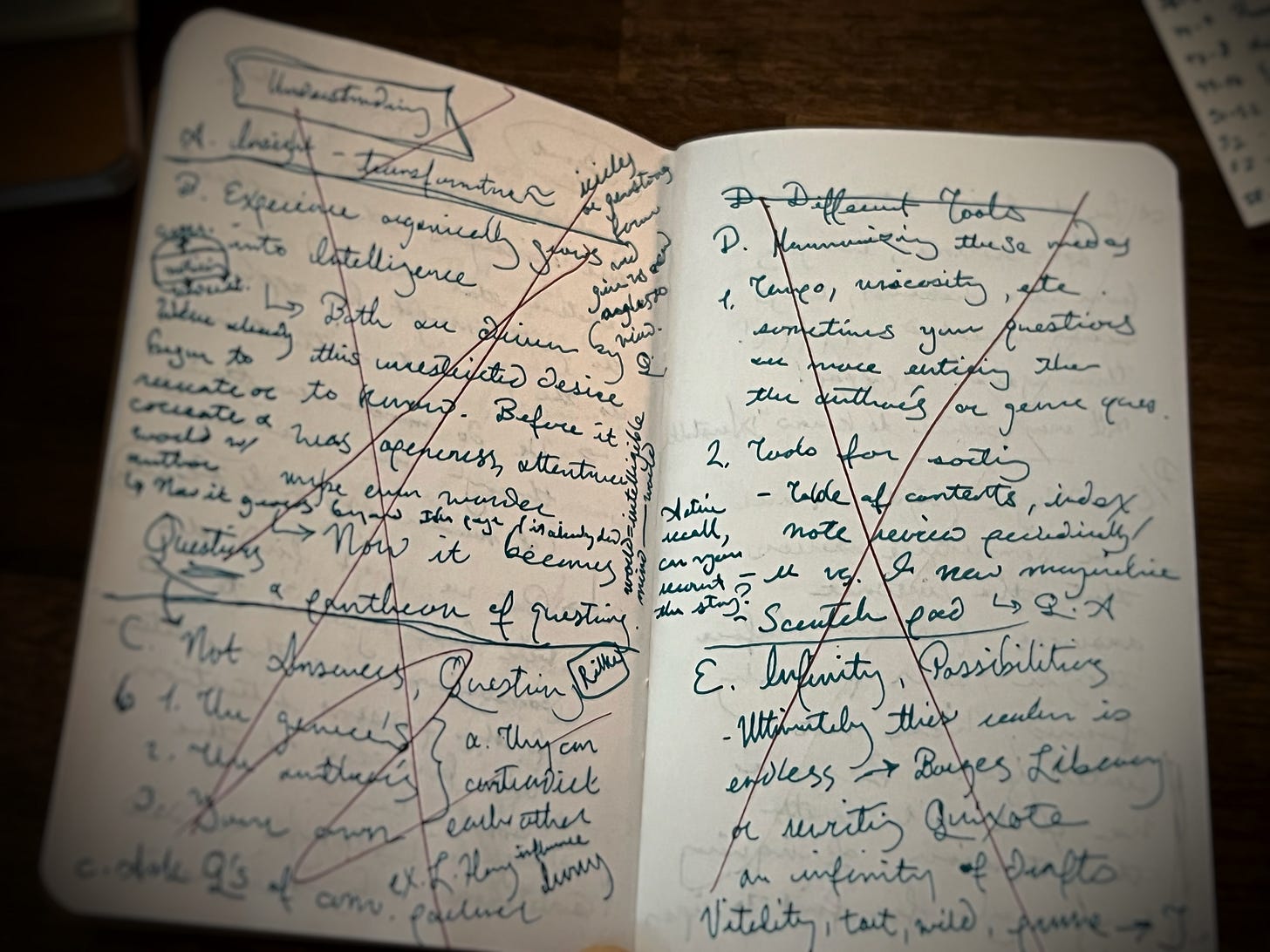

My process begins before I’ve even finished my Catch-All notebook. As I leaf through its pages, sometimes I notice that the pages I’ve written are no longer relevant.

They might contain a packing list for a trip from which I’m now returned. Sometimes they hold an outline for an article that has since been published; maybe its idea morphed into something entirely different and that fuller idea lives on in some other notebook. Often times, I see I actually had nothing to say—I was writing for writing’s sake, venting with a pen, just breathing ink. However these irrelevant words got on those pages, I can now see that there’s nothing more to be done with them.

So I cross them out. With bold red ink, from top to bottom, those slashes let me know that I’m “Done” with that page. Out of all the concerns I have in my life, this page is not one of them. My eyes have been divested of the responsibility of mining this page for insights. Like a policeman at a crime scene, the red hands of these X’s motion me towards the next page, while saying, “Move along, sir. Nothing to see here.”

Perhaps this comes across a bit ruthless. After all, we notebookers put so much care into our notes: the hues of the ink; the strokes of our penmanship; the thickness and smoothness of the paper; occasionally even the quality of our thoughts. But calling things “Done” means the words have fulfilled their purpose. They did their job well.

Nevertheless, you probably won’t cross out all of them. You have to to decide what “Done” means to you, page-by-page.

When it comes to more permanent records—like a Planner (⊞) or a Journal (≈)—I wouldn’t advise marring your pages in this way. With those notebooks, there’s not always a clear sense that you are “Done” with an entry. Different rules apply to different notebooks.

Migrations

Again, today we’re talking about Catch-Alls (⨁). In these intermediate places, we temporarily grab ideas before developing them somewhere else. They hold the seeds of larger ideas, and we should find better soil in which to scatter them, so they might actually grow into something. Pocket notebooks make for rather cramped pots.

Besides crossing pages out, there are other ways of processing them. Some of these seminal ideas you’ll want to migrate to another area. If I wanted to move that packing list to your Planner (⊞), I’d use a Migration Arrow to remind me to add it there: ↑⊞. If I want to flesh out an idea through a free-write session in a Journal (≈), I use another arrow to remind me to do that: ↑≈. If I take an idea into my blog editor to be published (≡), I use another arrow to let me know it lives there now: ↑≡. In most of these cases, once I’ve done the migration, I cross out the page.

If you’re “done” with a page, cross it out: ✗

Migrate any ideas that belong in another format, ex. ↑⊞, ↑≈, ↑≡, etc.

If the migration is complete and you’re “done” now, cross out that page.

Again, you don’t have to cross things out if you don’t want to. You might not be “Done” with that page yet. I just find that my future self is grateful anytime my past self takes something off his plate. It might feel like you’re killing your darlings, but we’re actually helping these ideas move along in their development.

Now, let’s deal with those remaining pages.

The Back Index

Logging Entries

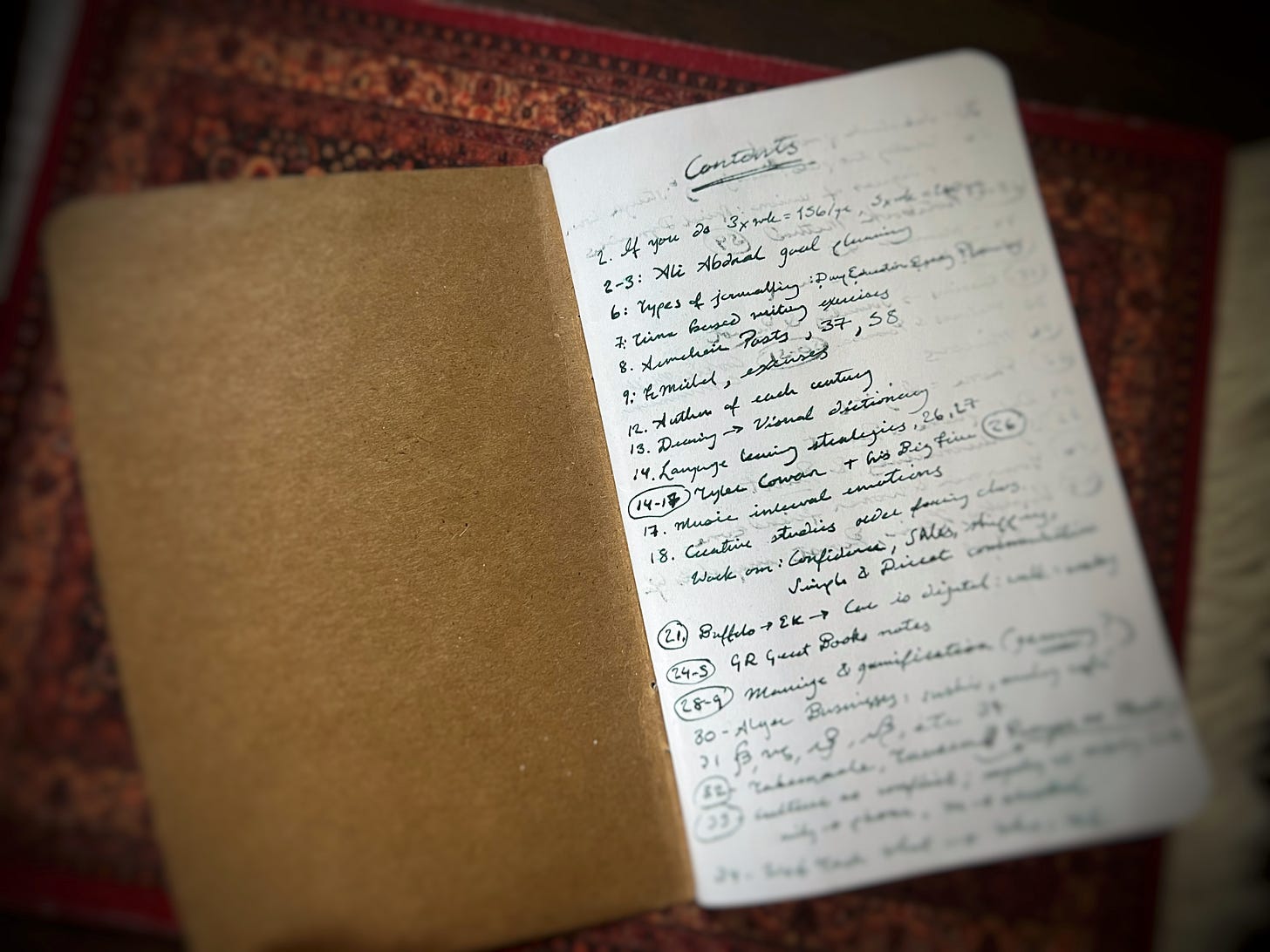

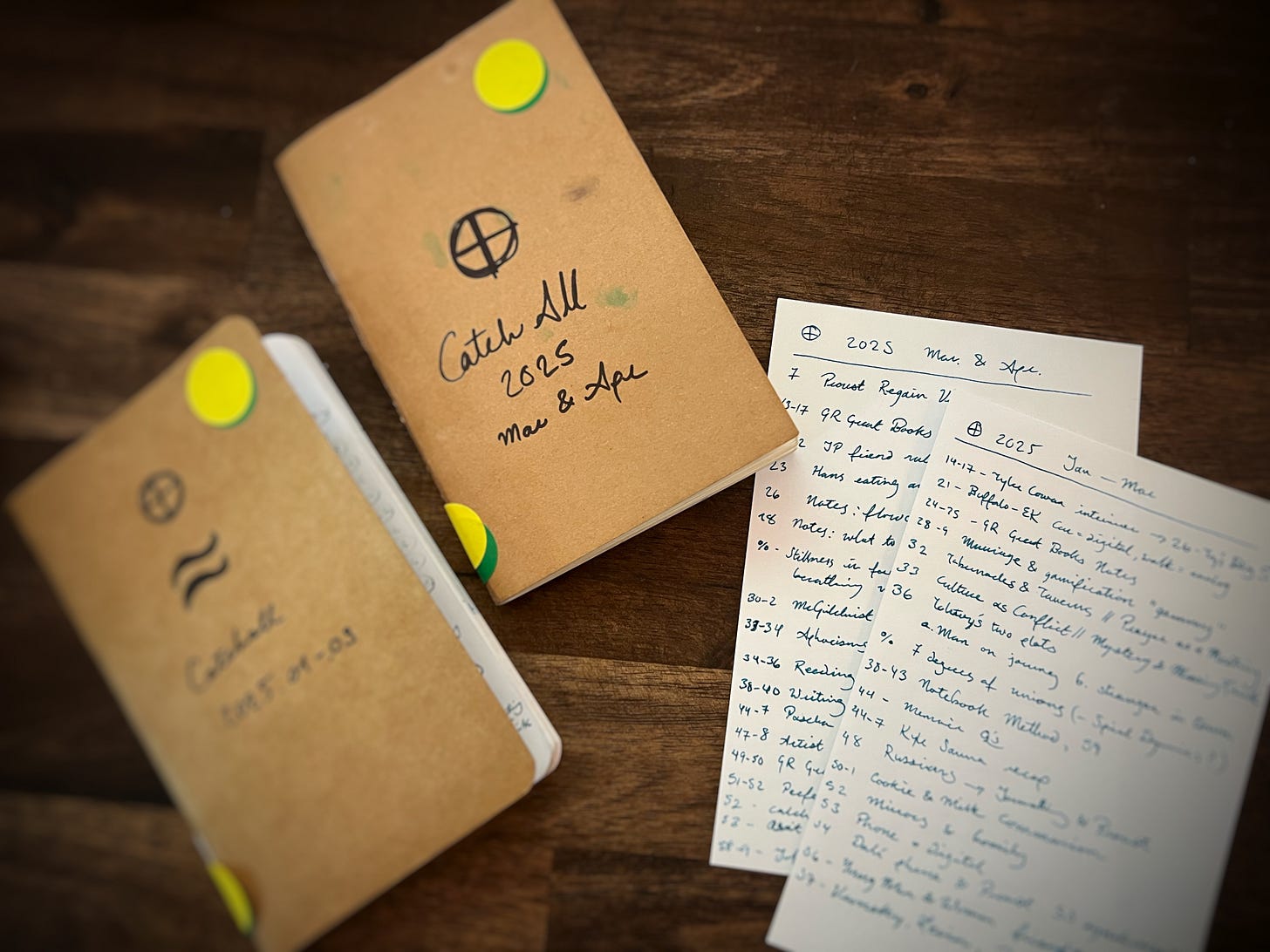

Now we’re going to log our remaining ideas in an Index. Usually this covers the last 2-to-3 pages in the back of my notebooks. But the front works as well (as you can see in the picture above.) Since most pocket notebooks sadly lack page numbers, I always begin by scribbling them in the corner of each page. Once I’ve numbered all the pages, I do a simple entry of the pages that haven’t been crossed out. Each entry is a page number and a few keywords to jog my memory of what lives on that page.

Technically, this is a “Table of Contents” rather than an “Index.” The current BuJo-Leuchtrrum parlance has conflated the two terms. Since “Index” has fewer syllables, I prefer to use it. Real keyword indexes are time-consuming to do the right way, and they’re honestly overkill for a notebook as small as a Catch-All. (Still, you can always do one later on if you want and this format will make it easier.) At this stage, we just want to see what the contents of this notebook are—at a glance.

You don’t need to wait until you’ve filled your notebook to start indexing it. Typically, I let a page hang around a little while before logging it, because I never know if it will be crossed out before I’m done with the notebook. Thus, my preference is to log pages when I’ve finished the notebook or during a regular review period. But if you want to log as you write, I recommend crossing out the entry in the Index, whenever you cross out the page. It gives a thrill of accomplishment to see items in an Index crossed out.

Prioritize Entries

Now, we’re going to prioritize our entries. After you’ve listed all the relevant pages, circle the ones that are most important for you. While all entries might be interesting, some are important. Maybe it’s an idea for a short story; maybe notes from a podcast or lecture; maybe a fledgling poem; maybe it was a significant journal entry. Whatever pages you feel are worth revisiting, circle their page number. We were ruthless earlier, so we could be precious now. There are some pages we’re done with. There are some pages that aren’t done with us.

Label Notebook 🟢

Once our indexed is logged and circled, I like to place a green sticker on my notebook. I put one on the spine and one on the cover (in case the one on the spine occasionally falls off). Whenever my eyes look at my notebook shelf, I can easily see which ones have been indexed and are ready for me to revisit. All those little green dots take quite a burden off of me. They let me know that I no longer need to hunt page-by-page to find meaningful entries. All I have to do is glance at the Back Index.

For a normal Catch-All (⨁), Phase One (🟢) usually takes me less than a half hour to do from scratch. Again, Planners (⊞) and Journals (≈) take much longer and work a bit differently. (More on that in another post.) Here are the steps for Phase One:

For the remaining valuable ideas, create an index at the back of each notebook:

Number all your pages (if you haven't already)

Log all pages that haven’t be crossed out.

Cross out any Index entries whose pages have since been crossed out.

Circle the especially rich pages you’d like to revisit.

Place a green dot (🟢) on the notebook's cover and spine.

Now, lets take this distillation to another level.

Index Your Index (With an Index Card)

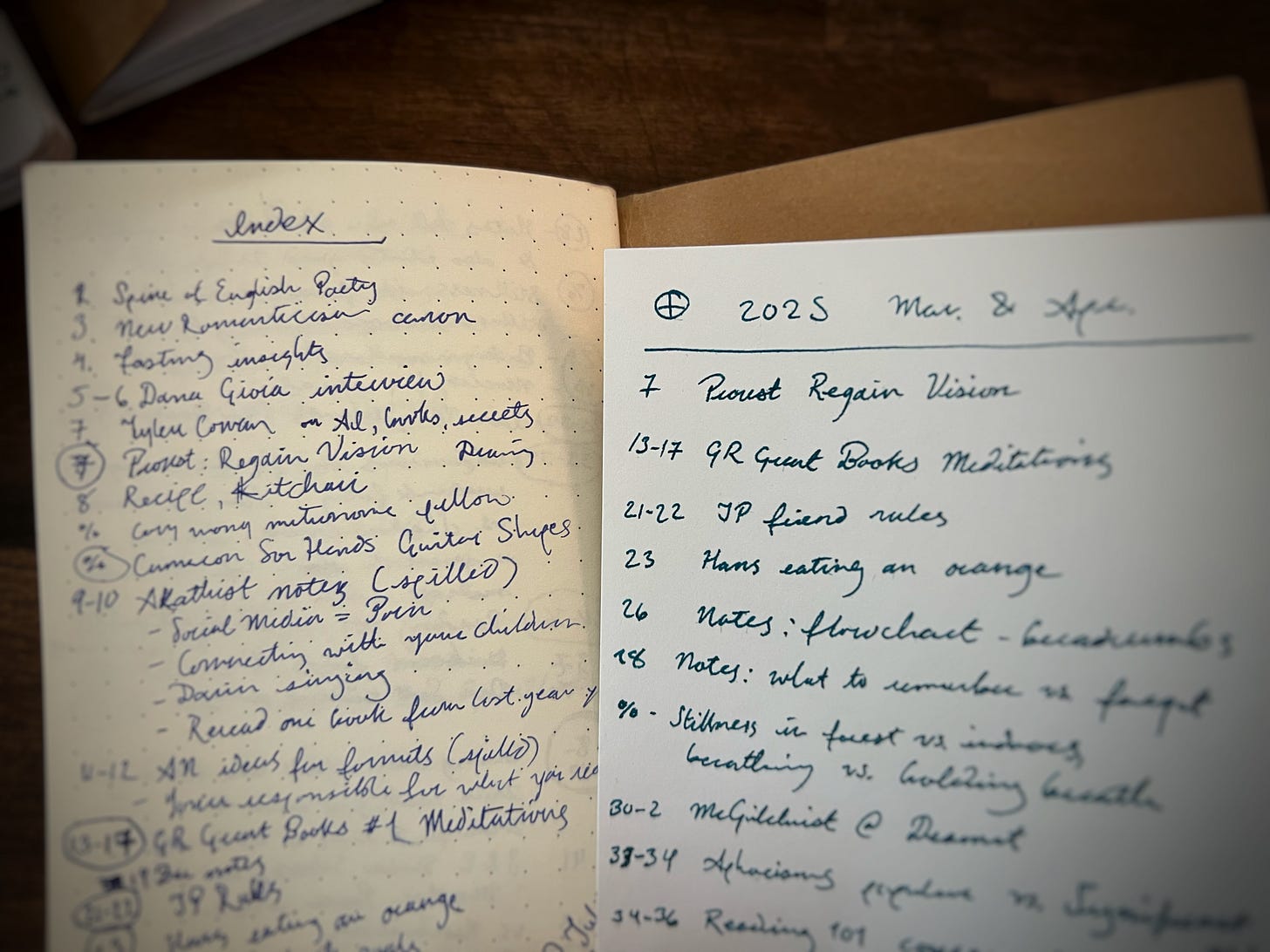

It’s been a few weeks you’ve been looking at your notebooks with their row of green dots on their spines. When you have spare moments to catch up with yourself, you enjoy opening up to an Index and seeing a handful of interesting entries. Maybe one entry reminds you of another one, but you can’t remember which notebook it was in: Is there an easier way to compare their contents? Whenever you’re ready to process your Catch-All to the next stage, grab an index card and some yellow stickers.

We call them “index cards” and yet we never use them for indexing. Let’s change that. Open your notebook to its Index and look at all the circled pages. Now, enter each of those pages on your index card. Since my index cards are 4x6, I can usually fit all the circled entries of a Catch-All on one side. Once all those most important entries are on the back of my notecard, I put a yellow sticker on the spine and the cover of the notebook, which lets me know I’ve processed this book up to Phase Two (🟡).

Now, whenever I look at my shelf I can see not only the books I’ve indexed (🟢), but the ones that have been entered on a separate index card (🟡). The upside to having a second card is that I can grab several years worth of important entries, lay them out on the table, and compare them.

From this vantage point, I can spot patterns easier than flipping through each physical book. Likewise, I can take a few of these cards with me and use them like writing prompts. They can even get wet, ripped, or wrinkled. I can always make another one based of the original Index in the book.

Each of these cards is formatted to give me not only the entries, along with the kind of notebook (in this case, ⨁) and the date of the notebook (ex. 2025 Jan–Apr). While shuffling through a handful of these cards, I can spot a few entries I want to revisit and—even if they’re in different notebooks—I can track down their original entries on my shelf, down to the exact page. I’ve just boiled thousands of pages down to a handful of index cards. I can breathe easier.

Here are the Steps for Phase Two (🟡):

Take only the circled pages from your Back Index

Log these highlights on a single index card (one card per notebook)

Place a yellow dot (🟡) on the notebook's cover

Maybe you’re old enough to remember that this ability to have a stack of cards that help you navigate materials in your library is nothing new…

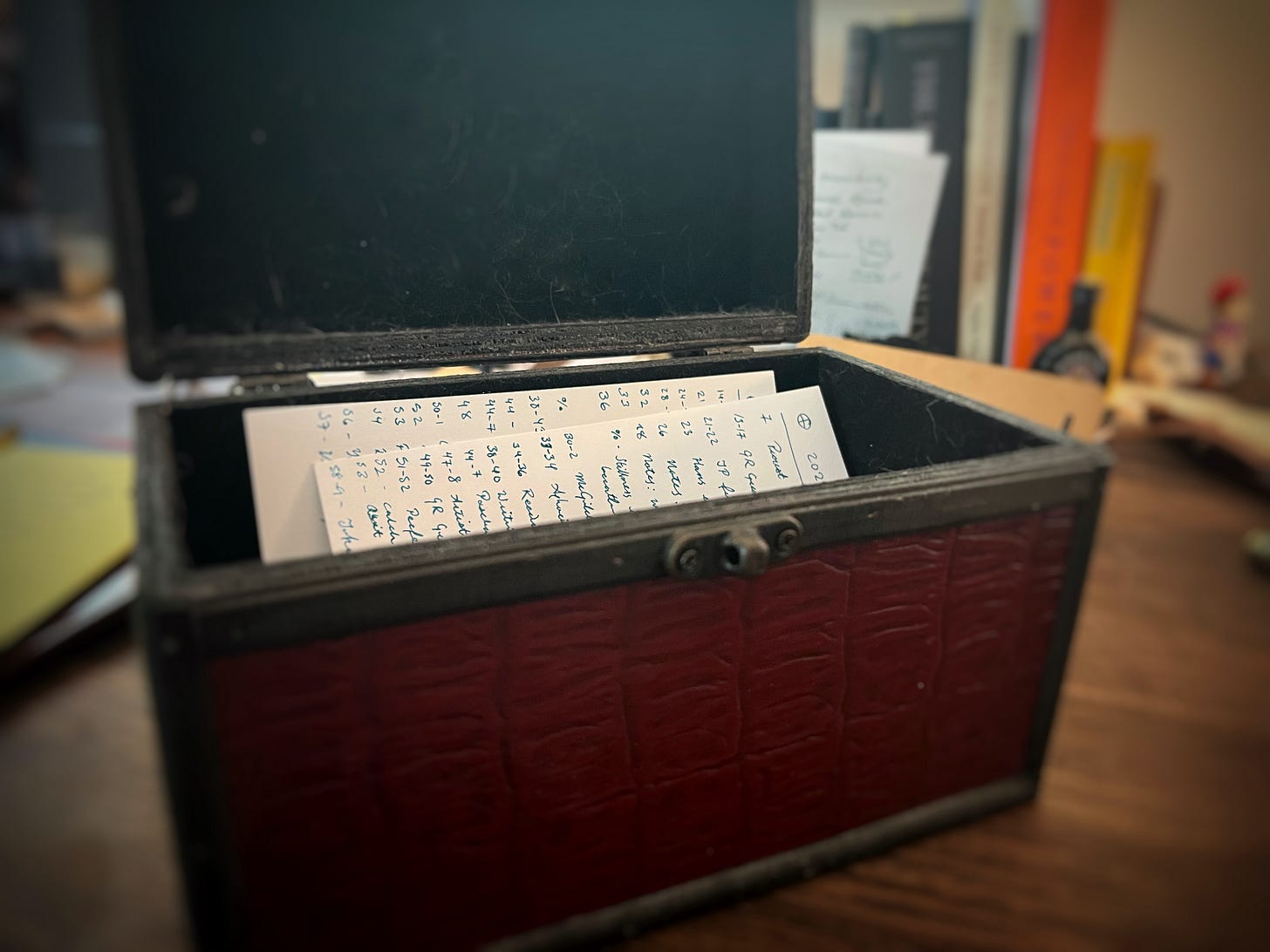

Your Card Catalog

When I was growing up, libraries had physical card catalogs which told you where books were to be found. You would page through them until you found a book to explore, and its numbers would point you to the right shelf. Likewise, you can stash your Index Cards in a recipe card box, and voilà you have your own Card Catalog.

First of all, the Card Catalog works in the traditional direction—what I call the “Reverse Direction.” You can grab any of these ideas, and work your way back to the original Catch-All notebooks and even further back to the exact page number of the original entry. Then you can pick up where you left off.

But the Card Catalog also represents a list of prioritized topics that also move us in a “Forward Direction.” All of the ideas here have been vetted by a few levels of distillation: you wrote them, you read them, you didn’t cross them out, you indexed them, you prioritized them, and finally you transferred them. If ever you’re looking for something interesting or meaningful to explore, here’s an entire box full of ideas that have already proven themselves worthy of you time.

Where Do We Go From Here?

This system is still in progress. Maybe we will continue to process these notes until we consider them completely “Done”—a row journals clad in red dots signifying our mastery over their contents (🔴). Then again, maybe we’re never truly “Done” with anything, nor would we ever want to be.

Instead, we might take this stack of important entries and notice themes that run throughout them. Rather than dealing with them in isolation, larger patterns could emerge. We could chain various entries—and even different notebooks—together through common keywords like: Proust, ⨁ 2024.05:23-4, ≈ 2024.01:33-36, etc). From here we could make a proper Zettelkasten or Commonplace of our own thoughts, and those we’ve come across from others.

But we can deal with all of that stuff another day. For time being, enjoy reviewing your Catch-Alls and knowing that their contents weren’t simply captured but curated. Now, those ideas are ready whenever inspiration moves you.

As ever,

Sam

Great system! So I have a whole chest of old notebooks and journals. Have you/do you recommend working backwards through old content or just making a fresh start of it? Mine go back decades so there’s obviously a lot that are probably not worth going through except for nostalgia.

I really enjoyed reading about your system! In an amazing coincidence, I wrote this morning about what I'm doing with my physical notebooks. While I also have a stack of catch-alls and planners, I'm focused on my journals, and the solution I'm trying is using AI to digitize and organize them: https://bdewey.substack.com/p/notebook-index

Have you ever thought of trying to bridge your paper records with digital?