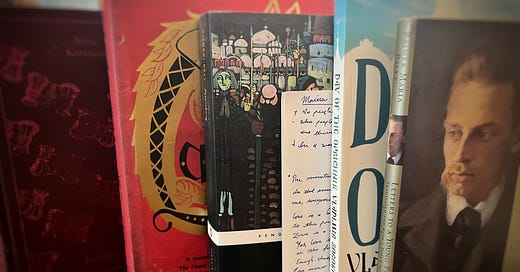

January 2025: Armchair Notes

Reading Russians during these cold, wintry months: Tolstoy, Bely, Vodolazkin, Tsvetaeva, Sorokin, and some Rilke as well.

In being true to the name of this blog, here are a few notes about books I’ve finished this month. Along with a few initial impressions of my own, I’ve also included a quote to whet your appetite. In the comments below, let me know:

What you read last month? What you’re looking forward to reading this month?

Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy

Tolstoy can write everything—but a title. Most people don’t seem to know that Anna’s story makes up only half of this novel. Her passionate and destructive romantic life is paralleled and balanced by the story of Levin’s growth a husband and father. He’s a realist who dives into working hard; he grows by that endurance and commitment past many doubts into being a faithful husband and a father. I’m so glad I finally got around to reading this—especially as a husband and father. Tolstoy is an absolute master. I could sympathize with all of his characters; I could see myself drinking tea during tense conversations; I could feel the summer breeze on my skin after mowing the meadows all day with my scythe. I’m not sure what title I would give the work instead, but now I heartily recommend Anna Karenina to everyone all the same.

All the girls in the world were divided into two classes: one class included all the girls in the world except her, and they had all the usual human feelings and were very ordinary girls; while the other class -herself alone- had no weaknesses and was superior to all humanity.

***

Levin had often noticed in arguments between the most intelligent people that after enormous efforts, an enormous number of logical subtleties and words, the arguers would finally come to the awareness that what they had spent so long struggling to prove to each other had been known to them long, long before, from the beginning of the argument, but that they loved different things and therefore did not want to name what they loved, so as not to be challenged. He had often felt that sometimes during an argument you would understand what your opponent loves, and suddenly come to love the same thing yourself, and agree all at once, and then all reasonings would fall away as superfluous; and sometimes it was the other way round: you would finally say what you yourself love, for the sake of which you are inventing your reasonings, and if you happened to say it well and sincerely, the opponent would suddenly agree and stop arguing. That was the very thing he wanted to say.

Laurus, by Eugene Vodolazkin

I read this story when it first came out in English translation almost a decade ago. As someone who gravitates toward more florid and mellifluous prose, I was struck by the spartan and rustic quality of Vodolazkin’s writing. But this simple, peasant language really shines when it gives itself to poetic juxtaposition of feelings and observations. Often I was stunned by these. It was even better the second time around (and now I’m reading his History of the Island). There’s a dreamlike quality to Laurus—you really get inside the mind (and the senses) of a Holy Fool. The lack of quotation marks allows you to slip between descriptions and dialogue as fluidly as our protagonist slips between being Arseny, Ustin, Amvrosy, Rukinets, or Laurus. In the end, that’s the book’s whole point: as human lives and human histories are brought into God’s eternal moment, we find ourselves and all our moments united within one another.

Life resembles a mosaic that scatters into pieces. Being a mosaic does not necessarily mean scattering into pieces, answered Elder Innokenty. It is only up close that each separate little stone seems not to be connected to the others. There is something more important in each of them, O Laurus: striving for the one who looks from afar. For the one who is capable of seizing all the small stones at once. It is he who gathers them with his gaze.

St Petersburg, by Andrei Bely

Nabokov said that there were four masterpieces of 20th Century prose: “Joyce’s Ulysses, Kafka's Transformation, Biely's Petersburg, and the first half of Proust’s fairy tale In Search of Lost Time.” While no one needs to be told to read Joyce, Kafka, or Proust—I’ve never heard anyone even mention Bely. Like Laurus, this book reads like a dream. Bely’s use of repetitive words turns this novel into one long sestina—red domino, cylinder hats and bowlers, caryatids, polypedal things, sardine tin, the spires of Sts Peter and Paul, tall strangers, and of course the ubiquitous mist, clouds, and shadows. It’s hypnotizing. Following this novel, I’m currently revisiting one of my favorite works of theology and philosophy, The Pillar and Ground of Truth, by Bely’s friend and fellow Symbolist, Fr Pavel Florensky. But more on that next month…

A Petersburg street in autumn permeates the whole organism: chills the marrow and tickles the shuddering backbone; but as soon as you come from it into some warm premises, the Petersburg street runs in your veins like a fever.

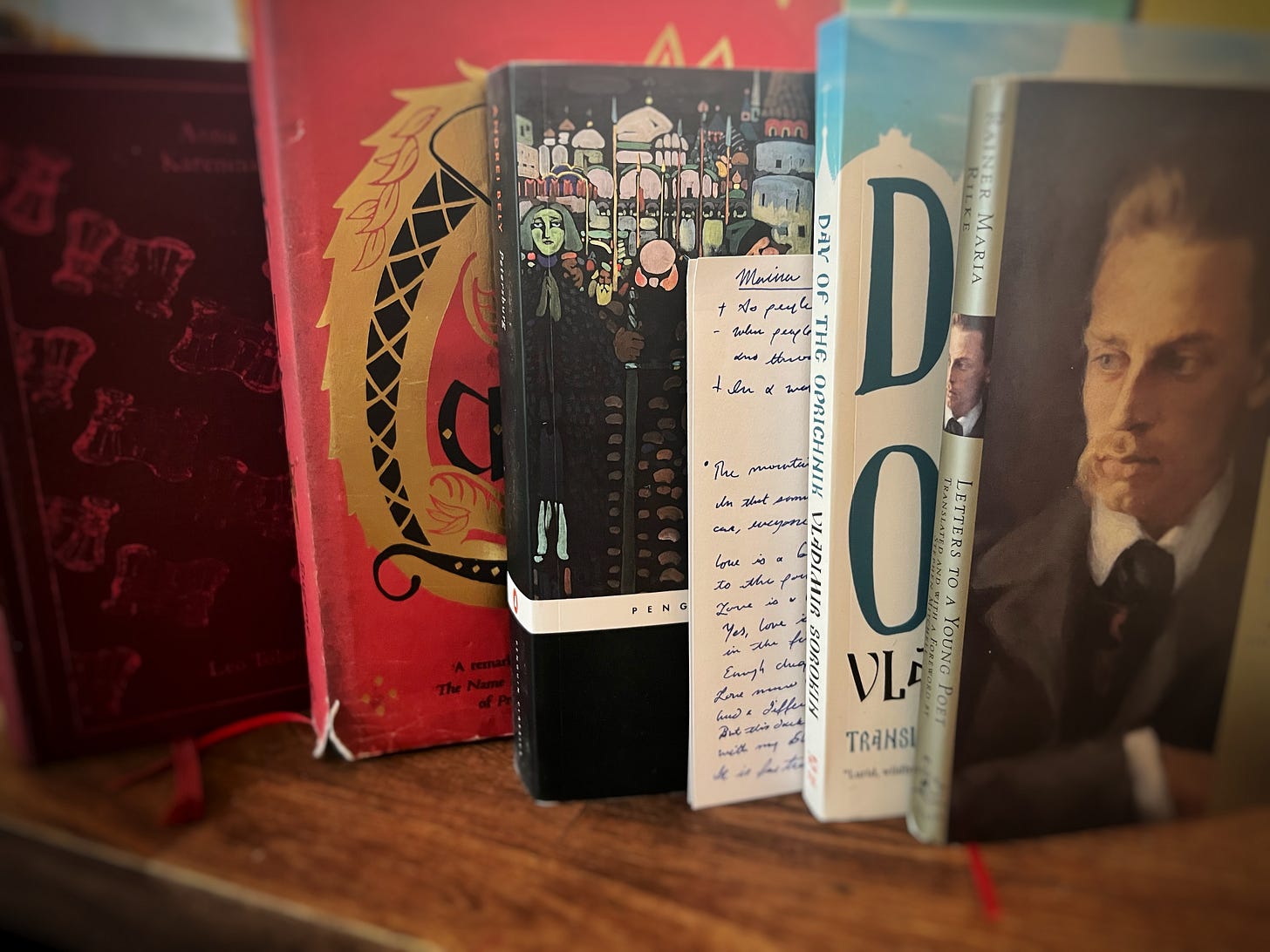

Selected Poems, by Marina Tsvetaeva

Readers of this blog will have noticed that Rilke is my favorite poet. Since I’m in a season of reading Russian writers, I asked my Russian friends who is your “Rilke”? (As it turns out Rilke was himself at times a Russian Rilke.) Most responded with either Anna Akhmatova or Marina Tsvetaeva. Having read a bit of Akhmatova last year, I decided to pick Tsvetaeva this time around. Like Rilke, many of her poems are driven by desire, no matter the thing she’s reflecting upon. Her sense of place, her friends (poems or Akhmatova and Blok), and sense of whimsy and humor (“Desk” and “Attempt at Jealousy”) also made an impression on me.

Moscow, what a vast

hostelry is your house!

Everyone in Russia is—homeless,

we shall all make our way towards you.With shameful brands on our backs and

knives—stuck in the tops of our boots,

for you call us in to you

however far away we are,because for the brand of the criminal

and for every known sickness

we have our healer here,

the Child Panteleimon.Behind a small door where

people pour in their crowds

lies the Iversky heart—

red-gold and radiantand a Hallelujah floods

over the burnished fields.

Moscow soil, I bend to

kiss your breast.

Day of Oprichnik, by Vladimir Sorokin

While I would not recommend anyone read this book, I must admit it’s well written. Among modern Russian writers, Sorokin seems to me to be the enfant terrible—like a Russian Michel Houellebecq. In this satirical work, Sorokin blends themes of sex and power together to make his political critique of an ascendant modern Russian imperialism. Most readers would probably say this all gets too gratuitous and obscene, and he would probably respond: “Yes, that’s exactly the point.” It definitely got under my skin, so I suppose he accomplished what he set out to do.

“Andrei Danilovich, the oprichnina is capable of miracles.”

”Madame, the oprichnina creates the Work and Word! of the state.”

”You are one of the leaders of that mighty order.”

”Madame, the oprichnina is not an order, but a brotherhood.”

Letters to a Young Poet, by Rainer Maria Rilke

This is a desert island book for me. I’d bind Rilke’s letters into my Bible along with those of St Paul. This is a cult classic among writers and artists, and it deserves all the praise it gets. Anyone who picks up a pen should read it. Scratch that. Everyone should read it. Creativity, the world, love, God, religion, time, books, poetry, restlessness, solitude—Rilke put the whole world into short letters. It never gets old. It always keeps me young. I’ll read it every year.

You are so young, so before all beginning, and I want to beg you, as much as I can, to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves—like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given to you because you would not be able to live them. The point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.

Links

Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy

Laurus, by Eugene Vodolazkin

History of the Island, by Eugene Vodolazkin

St Petersburg, by Andrei Bely

The Pillar and Ground of Truth, by Fr Pavel Florensky.

Selected Poems, by Marina Tsvetaeva

Day of Oprichnik, by Vladimir Sorokin

Letters to a Young Poet, by Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke’s Russia, by Anna A. Tavis