Don Quixote: The Greatest Novel You Still Haven't Read

Without a doubt Cervantes' masterpiece deserves every bit of praise it's received—it also deserves more readers. Let me convince you to pick it up.

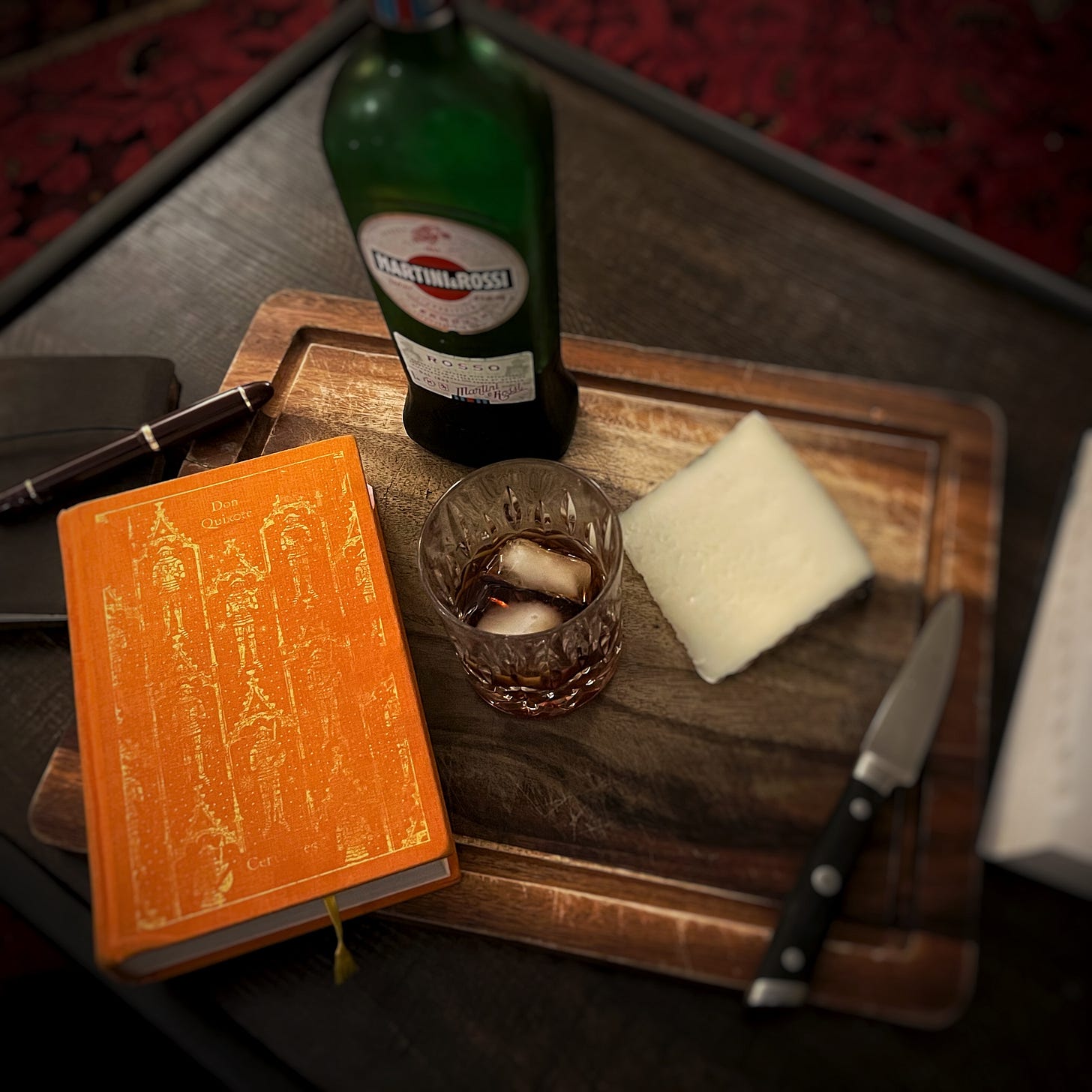

Here are some initial thoughts from my recent reading of Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. (Regarding translations: I highly recommend the Rutherford translation from Penguin. I look forward to reading Edith Grossman’s next.)

Don Quixote & The Trains in Spain

In May of last year, my wife and I traveled by train throughout the Spanish countryside. With our son about to be born that July, we were enjoying a glorious babymoon in that land of ibérico ham, flamenco guitars, and Moorish castles.

Barcelona greeted us with so many buildings adorned with vibrant tiles that the whole town gently glimmered like polished sea glass strewn across the shore. Madrid showed itself to be a home for both the refined and the rustic; a prince would be just as at home in the opulent opera house or the palatial gardens as any peasant would be while enjoying a glass of vermut de grifo and some slices of Manchego. The dizzying geometry of the tilework in Seville's Royal Alcázar mesmerized us; we lost ourselves in the countless arches of Córdoba's mezquita; we gazed for miles from the hills of Granada. Finally, we found a passionate dance of love and death on full display in Andalusia, from the Sunday bullfights to the siguiriyas of the gitanos. Spain is a culture so beautiful and energetic, it's almost maddening.

Aside from my beloved wife and my unborn son, my dearest companion on that trip was that ingenious hidalgo himself: Don Quixote de la Mancha. As the train carried us from Catalonia to Castile, I began reading the story of that famous knight-errant and how after “so little sleeping and so much reading, his brain dried up and he went completely out of his mind.” I slapped my leg reading about the priest and the barber evaluating Quixote’s library and throwing the most corrupting volumes in the fire. (Sparing, of course, those works written by a gifted author by the name “Cervantes.”) As I watched the rocky horizon of La Mancha undulate outside the window, I kept my eye out for any windmills or giants. By the time the train pulled into the station, I had a double revelation: Not only had I just discovered one of the most delightful books of my life, I felt I had met a real friend in this book.

Everything We Call Our Own Was First His

Cervantes’ Don Quixote is not only one of the greatest works in the Western canon but also one of its most under-appreciated. Despite widespread acclaim, few tackle it cover-to-cover. For many, El Quijote looms as a literary mountain too massive even to be attempted. Instead, they laud it from a distance, heaping empty epithets upon it, praising it as “the first modern novel.” Meanwhile, they simply carry in their impoverished minds that plebeian image of him as some quaint yet foolish elderly man tilting at windmills. But he has so much more to offer—and one who has never read Don Quixote will ever lack a full education.

I, mister barber, am not Neptune, the god of water, nor am I a madman trying to make people believe me sane; I am merely striving to make the world understand the delusion under which it labours in not renewing within itself those most happy days when the order of knight-errantry carried all before it. But these depraved times of ours do not deserve all those benefits enjoyed by the ages when knights errant accepted as their responsibility and took upon their shoulders the defence of kingdoms, the relief of damsels, the succour of orphans and wards, the chastisement of the arrogant and the rewarding of the humble.

The modern world owes much to this knight who spent his life trying to revive the medieval world. While many authors might toy with their characters or events in their stories, Cervantes was unique in toying with his own authorship. Don Quixote is a fiction woven together out of fictions. The narrator claims to have discovered the story in scraps of manuscripts (which never existed); he supplements his story with translations of a work initially penned by the Moorish historian Cide Hamete Benengeli (who never existed). If Cervantes had never delighted in these imaginary layers of textuality, we probably would never have Jorge Luis Borges. Naturally, we wouldn't have Borges' own masterful musing on authorship and his tribute to the originator of the concept in “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.”

Lest his novel devolve into endless retellings of retellings ad infinitum, Cervantes also turns the narrative back in on itself. Several years after the publication of Don Quixote, Part I in 1605, a unauthorized sequel appeared, authored by the enigmatic Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. While the author's true identity remains elusive, the literary merit of this Aragonese work has been settled: it was shoddy at best.

Spurred on by the spurious sequel, Cervantes responded by publishing his genuine Part II in 1615. A conventional author might have merely dismissed the inferior work with a corrective remark and continued on with his own narrative. But Cervantes was anything but conventional. Naturally, the narrator subtly mock’s Avellaneda’s sequel throughout Part II. But it’s not just the narrator. The story’s own characters join in the criticism as well:

Sancho had hardly uttered these words when two gentlemen, for such they seemed to be, entered the room, and one of them, throwing his arms round Don Quixote’s neck, said to him, “Your appearance cannot leave any question as to your name, nor can your name fail to identify your appearance; unquestionably, señor, you are the real Don Quixote of La Mancha, cynosure and morning star of knight-errantry, despite and in defiance of him who has sought to usurp your name and bring to naught your achievements, as the author of this book which I here present to you has done;” and with this he put a book which his companion carried into the hands of Don Quixote, who took it, and without replying began to run his eye over it; but he presently returned it saying, “In the little I have seen I have discovered three things in this author that deserve to be censured. The first is some words that I have read in the preface; the next that the language is Aragonese, for sometimes he writes without articles; and the third, which above all stamps him as ignorant, is that he goes wrong and departs from the truth in the most important part of the history, for here he says that my squire Sancho Panza’s wife is called Mari Gutierrez, when she is called nothing of the sort, but Teresa Panza; and when a man errs on such an important point as this there is good reason to fear that he is in error on every other point in the history.”

With this effortless weaving of self-referentiality in Part II, Cervantes prefigures our own age of postmodern media. Quixote is not only a character in a story, but he also becomes a celebrity for the role he plays in that story—and the role that story plays in society. There is something of Part II in self-reflective movies like The Truman Show and Synechdoche, New York. When our protagonists wrestle with being protagonists—or wrestle with their stories being ill-told—we hear an echo of Quixote.

It makes one wonder. Without the episodic exploits of Don Quixote, would we have the series-after-series of reality television? Would we have the legions of social media influencers reveling in being watched? Would we have Monty Python breaking the fourth wall and killing off the animator right before the hand-drawn monster catches our heroes? Would we have the countless turns to the camera from self-aware characters such as Pam and Jim in The Office? In the end, Don Quixote was not only the birth of the modern—it was the birth of the postmodern as well.

The Novel that Swallowed the World

If I had never read those first chapters on the train between Barcelona and Madrid, I might have remained among the unenlightened masses who have never experienced the life of Don Quixote. For the past year, I've looked forward to setting aside time to read the whole history of the greatest knight-errant who never lived and yet is more alive than most. Finally, this past September overflowed with Quixote's grandiloquent diatribes, the patchwork proverbs of Sancho Panza, and their countless misadventures. Since closing the book, questions of sanity and sanctity have continued to occupy my thoughts as of late. And, of course, I'm perpetually amazed by the brilliance of Cervantes and how masterfully he employed these literary devices even as he debuted them.

Yet, however much the author tinkered with the narrative artifice, he never eclipsed the humanity of his story. Throughout it all, the feeling that Quixote and Sancho were somehow real was only magnified. Even if they weren’t “real,” something about them was “true,” and “the truth might be stretched thin but it never breaks, and it always surfaces above lies, as oil floats upon water.” Just as this novel has distilled truths from fictional manuscripts, non-existent translators, spurious sequels, and even its own reception, I feel Cervantes has swallowed up our whole world between these two covers. No matter how big a book Don Quixote might seem from the outside, I can assure you: it’s even bigger on the inside.

“Yet the truth of the matter is that just by recording my thoughts, my sighs, my tears, my worthy designs and my missions he could have written a volume bigger than all the works of El Tostado put together, or at any rate as big. Be that as it may, my understanding of the matter, my dear sir, is that to write histories and other books one needs a fine mind and a mature understanding. To tell jokes and write wittily is the work of geniuses; the most intelligent character in a play is the fool, because the actor playing the part of a simpleton must not be one. History is, as it were, sacred, because it must be truthful, and where there is truth there is God, because he is truth; and yet, in spite of all this, there are those who toss off books as if they were pancakes.”

Wonderful analysis. One of the things I found so striking about Don Quixote was how shockingly modern its sensibilities felt in many respects. I often slog through the classics on a first reading (a failure on my part, surely), but the novel seemed to reach out and grab me in a way pre-20th-century literature rarely, rarely does.