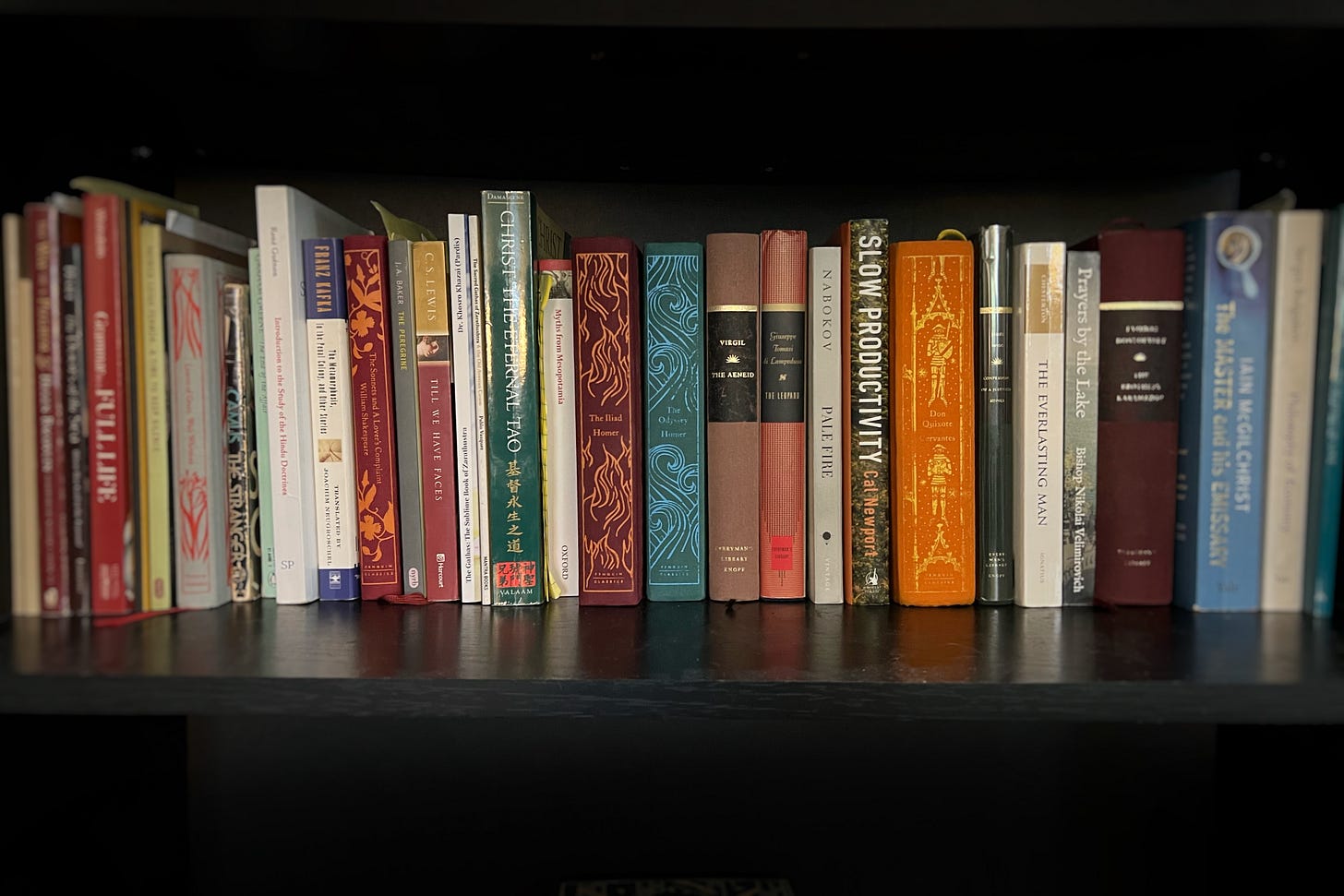

As we turn the page from 2024 to 2025, I’d like to flip back through all the pages I’ve turned over the past year. This year was particularly voracious season of reading for me. According to my Reading Logs:

I read 14,169 pages and 50 books in 2024.

June was the peak of my bibliophilic appetite, when I read 2,650 pages and 9 books in that one month. (I still regret not reading the extra 75 pages of Pride & Prejudice to make it an even ten.)

My largest book was Don Quixote in September, though there were many formidable tomes this year.

Many works were classics I’ve not thought of since my school days. Several I’ve dipped into or known in part, but finally have finished and now know in whole. Some were surprises I stumbled upon. Few were duds. Whether on the beach on summery afternoons or in the armchair during countless lamplit evenings, great books were always near at hand.

Above all, I'm grateful to those who have followed my reading journey since this blog’s inception in April. Beyond growing as a reader, I’ve evolved even more as a writer. While I look forward to sharing more with you in 2025, here are my final armchair notes from 2024. Cheers to another year of reading! 🍻

Highlights

The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Since the beginning of the year, this was the book I was most looking forward to finishing. It did not disappoint. Without question, this is one of the greatest books I’m likely to read in my life. For fifteen years I would’ve told you The Brothers Karamazov was one of my favorite books—even when I hadn’t even finished reading it. What I found in selections and sprints dramatically changed my life in those earlier years. Now, I’ve reached the summit of this literary mountain, and I look forward to hiking its paths many more times in the years of reading left to me on this earth, whose soil is perpetually kissed by Dostoevsky’s characters. Additionally, I’m grateful for how well-received my post on the novel’s chiastic structure has been; it’s helped many readers orient themselves in this wide and wild work. Good strength to anyone attempting the Karamazovs in 2025!

Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

If The Brothers Karamazov is the masterpiece everyone urges you to read, Don Quixote is the greatest novel too few recommend. While many classics of literature make you think, very few can make you smile like Quixote does. There are scholastic diatribes on the nature of various virtues, scrappy misadventures in the Spanish countryside, and poignant moments which make jaded moderns (such as myself) wonder if this delusional fool really has revived a bit of chivalry and wisdom in our world. Whether it was seeing their statues in Madrid or just encountering the vivid realism of Cervantes’ pen, by the end of the book I refused to admit that Quixote and Sancho were fictions. Like Sherlock and Watson—who I’m sure were inspired by Cervantes’ episodically epic buddy tale—these were that rare breed of characters who were simply too real to remain literary. Perhaps this is why the meta-literary question of literature and reality is baked into the very structure of Quixote. For more on that, read my post about “The Greatest Novel You Still Haven't Read.”

The Master & His Emissary, by Iain McGilchrist

“We’re only thinking with half of our brain—and it’s the weaker half,” would be my one sentence summary of McGilchrist’s axial thesis in The Master & His Emissary. Within any given moment our brain brings the two kinds of attention respective to its right and left hemispheres; these complimentary modes of experience give a meaningful stereoscopic quality to our lives—but our cognitive abuses have created an imbalance in our minds which is so ubiquitous we assume it’s normal. As a recent article from Dan Hitchens at First Things point out, McGilchrist is one of the only thinkers alive today whose thoughts could redefine an age of human thought. While I devoured this book during my grad studies over a decade ago, this time I took a more measured pace with McGilchrist’s ideas. Since the book is broken into twelve sections, a friend and I met once a month for a year; this prolonged and almost meditative pace helped the recurrent leitmotifs of McGilchrist’s though settle more deeply into us. One of my highlights of the year was meeting McGilchrist at his Hillsdale lecture, where he signed my (well-loved) copy of The Master & His Emissary and my (barely-cracked) copies of The Matter with Things. Next year, I’d like to offer essays on each chapter to encourage you in your reading of his groundbreaking work.

Philosophy of Economy: The World as Household, by Fr Sergei Bulgakov

This book has been a foundational text for me because of one idea: economic activity and artistic creativity are the same thing. Bulgakov offers an economic vision of the cosmos where creativity—be it human, divine, or “sophic”—revivifies a world that has fallen into a temporary state of death. At times, this was a very dense book, but it is always rewarding. Since his work leans so heavily on Schelling’s work of correlation—subject-object, organism-mechanism, spirit-material, freedom-necessity, life-death—there is much in Bulgakov that relates to McGilchrist’s left-right hemisphere work.

The Leopard, by Giuseppe di Lampedusa

While coming-of-age stories abound in literature, few works capture the end of an age with such grace. This beautiful novel follows a prince entering his golden years with elegance matching the prose itself. I'm grateful to have experienced it before the upcoming Netflix adaptation comes out.

Great Reads

Christ the Eternal Tao, by Hieromonk Damascene

What if someone emphasized the “Eastern” part of Eastern Orthodoxy? This book. While the second half of the book is a fairly comprehensive yet standard source book of mystagogy, the opening poetry is what I most look forward to revisiting. The spiritual significance of wu-wei and how it relates to hesychasm is something I’m still thinking about, months after writing my introductory post to those ideas.

The Embers & The Stars: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Moral Sense of Nature, by Erazim Kohák

As I write this list, I realize I never finished my third installment in the Vacation in Northern Michigan series! (Here is Part I: Day & Part II: Dusk) I assure you it’s not from lack of interest. After reading Kohák, I cannot look at the leaves on a branch or an empty glass on the counter without thinking about reflective anxieties, convivial kinship, and the moral significance of the natural world. This book pairs nicely with McGilchrist and Bulgakov. Be forewarned: his descriptions of woodchucks, beavers, and streams will make you want to build a cabin in the woods.

The Sun & The Steel, by Yukio Mishima

You need to work out. The study is no substitute for the gym—though the gym may be a substitute for the study. Mishima’s reflections on physicality and the eloquent vitalism of his prose are definitely worth exploring. That being said, his life and work did tragically tip over from the realm of paradox into contradiction. Read the post here.

Myths of Mesopotamia & The Gathas of Zoroaster

This year I was obsessed with how we ground our ideas in canons. While the Bible is the foundation for so many in this world, even it owes many of its literary forms and prophetic approaches to these sources. The epic form of Gilgamesh. The wisdom literature prophet of Zoroaster. Everyone from Homer to Moses to Nietzsche is indebted to these works, and they’re so rarely read in humanities departments. Even in their fragmentary state, there are countless diamonds in these roughs. Or lapis lazuli, as it were.

The Troifecta

A special project this year involved reading what I call the Troifecta: the Iliad, Odyssey, and Aeneid. While all share a common source in the Fall of Troy, each offers a distinct perspective: Achilles’ tragic tale, Odysseus’ nostalgic homecoming, and Aeneas’ refugee journey. Reading these as an adult revealed new depths: the ruinous nature of anger; the bonds between husband, father, wife, and son; the poignant quest to forge a new home. Each breaks the heart in its own unique way. These are not textbooks. If you’ve never read these outside of a classroom, I highly suggest spending a season with them.

Best Rereads

Till We Have Faces, by C.S. Lewis

This is perhaps my fourth or fifth reading. Every time it gets better. Despite Lewis’ often clumsy world-building, his spiritual maturity is unmatched in this novel. Orual is as frustrating as she is familiar.

The last time I read this book, I was in high school just discovering prayer ropes and icons. Now, I see again why this book is a perennial classic. I’m still catching up to it. This time through, I was struck by how much practical wisdom and sincerity the Pilgrim exhibits in such a small book. His simple, incessant prayer inspired me deeply this year. Also, many of you came to this blog through my review of it. That alone is worth my gratitude.

The Everlasting Man, by G. K. Chesterton

Speaking of reviews, my full review of this book will be published very soon in the New Year! Then again, “full” is perhaps not the right word—as this book covers so much. There are so many breathtaking passages and pithy witticism that I don’t know if I’ll ever tire of returning to this book. Indeed, I think it has much that our own age in history sorely needs. Brush off your copy and keep your eyes out for the review.

Disappointments

Pale Fire, by Vladimir Nabokov

Many people I trust for book recommendations laud this book. Perhaps it was burdened by my expectations. Overall, I don’t think unreliable narrators are interesting devices—since all narrators are ultimately unreliable. Nabokov is playing a game in this book and I don’t know if it’s fun enough to learn all the rules. In any case, it was enjoyable enough to make me want to give it another chance in the future.

Pride & Prejudice, by Jane Austen

Maybe it’s because I’m a man. Maybe it’s because I’m modern. This just didn’t land for me. Deciphering the characters’ overwrought pleasantries was a chore; the stakes weren’t always clear to me; people were frail; other readers told me to try reading it as satire. In the end, I told my wife the character I most identified with was Mr Bennett who wanted to be tucked away in his study away from all this tea cup drama.

Death Comes for the Archbishop, by Willa Cather

With as dramatic a title as this—what a boring book! The novel was decorated with so much kitschy devotional language and nugatory shibboleths, I couldn’t tell if the author was an excessively pious Catholic who didn’t know how to tell a story or a good enough writer with only a superficial grasp of Catholicism. If you’re a Catholic making a trip to the American Southwest, this might be your book. But it certainly wasn’t mine. If someone wants to write a detective story with the same setting and same title, I’ll give it another shot.

Best Poetry

The Sonnets, by Shakespeare

There’s a universal structure to Shakespeare’s sonnets. The first quatrain creates a world and introduces characters. The second builds the tension. The volta brings it all to climax and resolves it in the remaining quatrain. Finally, the heroic couplets sets things in order before sending you on your way. It’s a microcosm of all plots.

Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman

This was not written by some particular man with a long white beard in New England. This is our version of Song of Songs written by the Spirit of America itself. To live in this country without reading Leaves of Grass is to be ignorant of our native religion.

Prayers by the Lake, by St Nicholai Velimirović

For several years, I’ve been reading this book whenever I find myself by a body of water: Lake Michigan, Lake Leelanau, Lake Dillon in Colorado, Lake Como in Italy, The Tegernsee in Bavaria, etc. St Nicholai wrote some mystically insightful psalms in this collection from Lake Ohrid—with a surprisingly eclectic approach to spirituality and philosophy as well.

Before We Go

Thanks for reading along with me in the inaugural year of Armchair Notes.

In the comments below, please reach out and let me know:

What were the best things you read in 2024?

What are you looking forward to reading in 2025?

As ever,

Sam

Full List of Books Read (50)

The Meaning of Love

Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov

Philosophy of Economy

Sergius Bulgakov

Death Comes for the Archbishop

Willa Cather

The Brothers Karamazov

Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

Iain McGilchrist

The Resistance to Poetry

James Longenbach

Prayers by the Lake

Nikolaj Velimirović

The Didache

Anonymous

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner

James Hogg

Don Quixote

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

Cal Newport

The Everlasting Man

G.K. Chesterton

The Professor and the Siren

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

Pale Fire

Vladimir Nabokov

Deschooling Society

Ivan Illich

Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout

Cal Newport

The Leopard

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

Aeneid

Virgil

Pride and Prejudice

Jane Austen

The Odyssey

Homer

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

William Shakespeare

Christ the Eternal Tao

Damascene Christensen

The Gathas: The sublime book of Zarathustra

Zoroaster

Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others

Stephanie Dalley

Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold

C.S. Lewis

Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain

Maryanne Wolf

The Book of Minds: How to Understand Ourselves and Other Beings, from Animals to AI to Aliens

Philip Ball

Der, Die, Das: The Secrets of German Gender

Constantin Vayenas

Not Far from the River: Poems from the Gatha-Saptasati

David Ray

The Iliad

Homer

Small Things Like These

Claire Keegan

Shakespeare's Sonnets

William Shakespeare

The Peregrine

J.A. Baker

The Metamorphosis

Franz Kafka

The End of the Affair

Graham Greene

The Embers and the Stars: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Moral Sense of Nature

Erazim V. Kohák

Introduction to the Study of the Hindu Doctrines

René Guénon

The Meaning of Being Human

John D. Zizioulas

Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life

Oswald Spengler

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Other Tales of Terror

Robert Louis Stevenson

Grammar for a Full Life: How the Ways We Shape a Sentence Can Limit or Enlarge Us

Lawrence Weinstein

Leaves of Grass: The First (1855) Edition

Walt Whitman

A Time to Keep Silence

Patrick Leigh Fermor

Confessions of an English Opium Eater

Thomas de Quincey

The Stranger

Albert Camus

The Way of a Pilgrim and the Pilgrim Continues His Way

Anonymous

Tao Te Ching

Lao Tzu

The Doors of the Sea: Where Was God in the Tsunami?

David Bentley Hart

The Russian Idea

Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

Omar Khayyám